My newsletter, System Change, sets out to illuminate the international financial system, its impact on the lives and livelihoods of the world’s people; above all, its impact on the ecosystem. I am a political economist and I write for the general public and policy makers - not for practitioners of the ‘dismal science’.

In System Change you will find short and long-form pieces as well as my commentary on events as they unfold. I’ll share thinking for my upcoming book on the global financial system and also report on work I am doing as a member of the Scottish government’s Just Transition Commission - currently the only attempt by a government to prepare and plan for the coming transformation of both the economy and the ecosystem.

System Change is based on my experience of originating and leading a powerful global movement that led to the cancellation of $100 billion of debts owed by more than 35 low income countries - a campaign known as Jubilee 2000 or Drop the Debt. System Change will draw on the lessons I learned, as reflected in my books. These include The Real World Economic Outlook (2003), and The Coming First World Debt Crisis (2006) - for which I was mocked and dubbed ‘Chicken Licken’ - until the global financial crisis imploded the next year.

At the height of the financial crisis I co-authored - together with a dream team of environmentalists and ‘heteredox’ economists - the original Green New Deal (2007-8) - later adopted by the Sunrise movement in the US. The Green New Deal articulated our vision for ‘joined up thinking’ about the financial system and the ecosystem. This was followed up by my books, Just Money (2014), The Production of Money (2017) and then in 2019, The Case for the Green New Deal.

I hope the System Change posts will encourage readers to focus on the invisible, global financial system - made opaque by unjustified complexity and the deliberate use of language that aims to befuddle and confuse. There is logic behind the obfuscation. It hides the often fraudulent activities and immense power of those that have captured the system, make massive gains from it, and are now using it to extract, exploit and profit from the planet’s finite resources. Their greed will drive the ecosystem to destruction.

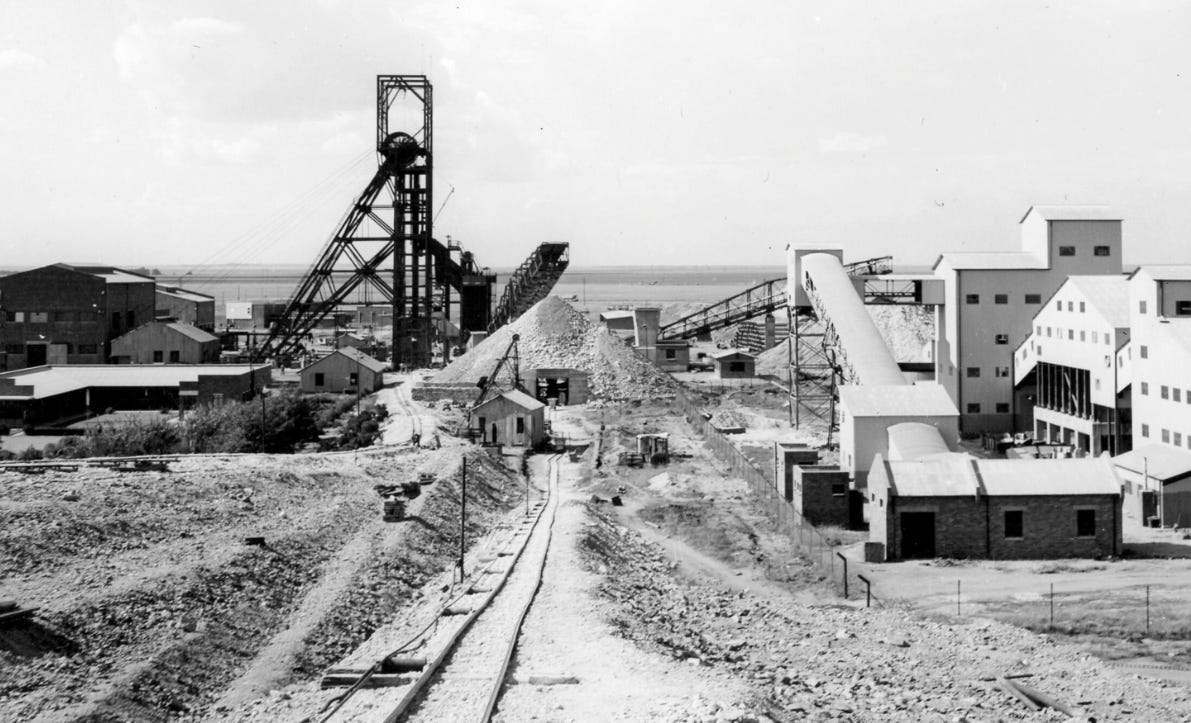

How did my fascination with global financial architecture begin? It was not an obvious subject for a young girl growing up in a small, remote gold mining town on the South African veldt.

President Steyn gold mine, Welkom

At about the age of 12 and on the daily seven-mile drive to school I pestered my Dad to explain why the price of our town’s only product – gold – remained fixed even while other prices rose or fell?

My father (who had left school early to captain heavy bombers during the war) struggled to explain the financial architecture of the Bretton Woods system to me. It was a system that had led, since 1934, to the fixing of the gold price at $35 dollars an ounce. That was not to change until 1971, when President Nixon unilaterally dismantled Bretton Woods…

Ever since I have had an intense interest in the architecture of the international financial system and how it impacts at a micro level on remote little places like my hometown, Welkom.

After University I was drawn to Tanzania by the leadership of President Nyerere. At the time this poor East African country was in conflict with South Africa, largely because Tanzania sheltered the ANC leadership. That experience of viewing racist South Africa and the rich west through the prism of life in a a very poor country in Africa, changed my perspectives on the world. It explains why I was so committed to the Jubilee 2000 movement for the cancellation of the sovereign debts of low income countries. Then, as a researcher and author at the New Economics Foundation (NEF), I reflected more deeply on the international financial system and its impact on sovereign debtor nations like Tanzania.

Along the way I came to believe that a society’s developed and stable monetary system represents a profound civilisational advance. I understood that money is not, and never was, a commodity, but a social construct, or social technology. As such, and underpinned by taxpayer-funded institutions, it was designed (albeit haphazardly over time) to “enable societies to do what they can do” as Keynes argued. In societies without a sound monetary system there literally is no money or trusted currency to enable the people to do what they can do. Those countries are invariably dependent on, and exploited by, the creditors, currencies and systems of richer, more powerful countries.

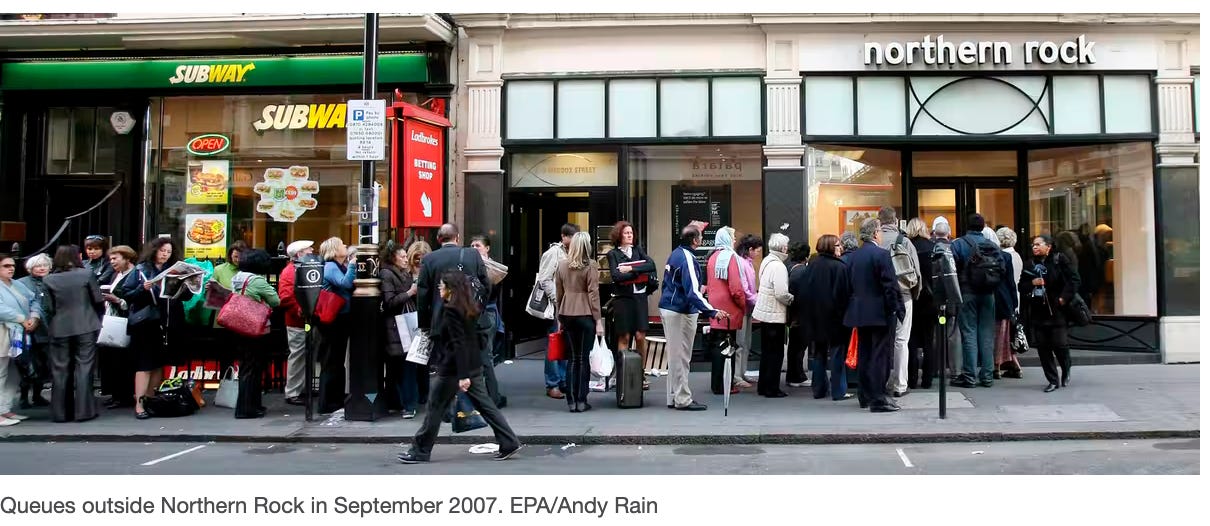

After the GFC I worried that so few economists and members of the public had been prepared for the financial crisis of 2007/8. This, I reasoned, was partly because most had little understanding of the fundamental nature of money, and even less grasp of the distinct roles and impacts on people’s lives made by both the domestic and international financial system.

The system had been developed by earlier societies (and individual geniuses like John Law) to act as servant, not master of the economy. Above all, societies invented and developed monetary systems in order to allow them to make, build and grow life’s vital necessities.

That is no longer the case. The international financial system has now been captured, and engineered to serve the interests not of society as a whole, but of the 1% - the wealthy. The 99% struggle for stable lives and decent livelihoods, and many are in revolt against the system.

I am now convinced that to stabilise both the world’s political and economic systems, as well as the global ecosystem we must transform the international financial system.

That is what System Change will be all about.