An honour, its meaning and memories

...starring Adam Habib, Zeinab Badawi, Bobby Kennedy, Mahatma Ghandi and the IMF.

It's high summer. I’m reviewing books, brewing tea in a beach hut, staring out at the sea, watching asset prices and prepping for the Berlin Climate Cultures event. But an unexpected honour has stirred memories and echoes - memories that demand to be recorded.

A few weeks ago the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) granted yours truly an honorary doctorate. The ceremony, attended by hundreds of new graduates and their families - was powerful and moving. The conferment was not just a great honour, but also had a very special meaning for me - embodied in the figures of SOAS Director Professor Adam Habib and SOAS President Ms Zeinab Badawi.

There I am, all dressed up in glorious technicolour and with a perky, tassled cap, seated with the university’s academic and strategic leadership. In the back row from left, Prof Claire Ozanne, Deputy Director, Prof. Adam Habib, Director SOAS and professor of political science, Lord Michael Hastings, CBE, Chair of the Board, Khadir Meer, COO of SOAS, and next to me, Zeinab Badawi, President of SOAS, and currently presenting the BBC’s “Take Me to the Opera”

Prof. Adam Habib

Until recently, Prof. Habib was Vice Chancellor of the University of Witwatersrand where, more than fifty years ago, I had gained my undergraduate degree in politics and economics. At that time, apartheid was deeply entrenched in all South African institutions and ‘Wits’ - as we called the university - was no exception. The university was an all-white centre of learning. The very idea of black students, never mind a black vice-chancellor, was anathema to the authorities, even while the academic body at Wits was perhaps the most progressive of South Africa’s intellectual hubs. Not only were black students banned from academic study, they were also banned from all student organisations. When leaders of the National Union of South African Students defied the government, fought segregation and affiliated black student organisations, they were banned. I belonged to the only mixed race student organisation permitted by the apartheid regime: the radical Anglican Students Federation - part of the University Christian Movement - tolerated because it was an inter-denominational religious body. Subsequently Steve Biko broke away from the UCM to set up a black students union - the South African Students Organisation. That too was later banned, and Steve Biko murdered by the apartheid regime in 1977.

While I was studying, the Wits student union, in a direct provocation to the apartheid government, invited US Senator Bobby Kennedy to visit. On the 8th June, 1966, I sat at the back of the Great Hall , as it was known, and listened in awe to his speech, which began:

What is the battle to which we are all summoned? It is first a battle for the future. The day is long past when any nation could retreat behind walls of stone or curtains of iron or bamboo. The winds of freedom and progress and justice blow across the highest battlements, enter at every crevice, are carried by jet planes and communications satellites and by the very air we breathe.

So tomorrow's South Africa will be different from today's – just as tomorrow's America will be different from the country I left these few short days ago. Our choice is not whether change will come, but whether we can guide that change in the service of our ideals and toward a social order shaped to the needs of all our people. In the long run we can master change not through force or fear, but only through the free work of an understanding mind – through an openness to new knowledge and fresh outlooks which can only strengthen the most fragile and the most powerful human gifts – the gift of reason.

Fifty six years later, in July, 2022, at the SOAS conferment of degrees and honours held in the Friends Meeting House, London, that future of which we had dreamt of was partially made visible. Prof. Habib’s elevation to Vice-Chancellor of Wits, and then subsequently to the post of Director of SOAS are signs of some, if still insufficient progress in that battle for South Africa’s future that Bobby Kennedy spoke of. According to Prof. Habib’s biography:

Transformation, democracy and inclusive development are fundamental themes of his research. Habib’s book South Africa’s Suspended Revolution: Hopes and Prospects, has informed debates around the country’s transition into democracy.

You will understand therefore why I struggled to hold back tears as he turned to me and made a short speech granting the honorary doctorate.

Here he is, delighting us all with a witty speech at a reception on the night before the conferment. Behind him, the musician Kadialy Kouyate on the Kora.

The Orange Free State (OFS), Mahatma Gandhi and the history of India

But there’s more to the story of Adam Habib, me and ‘South Africa’s Suspended Revolution”. To understand the full significance of Prof. Habib’s role in this ceremony, bear with me as I take you back to the 1950s and one of the most rural and backward regions of South Africa - the province of my childhood and adolescence - the Orange Free State (OFS). While I lived there Indians and Indian South Africans were forbidden by law from setting foot inside the province.

My father despised the apartheid system and its leaders, and explained the injustice of a nineteenth century edict that banned Indians passing through the territory by train from stepping down on to a platform - to buy food from station vendors. So I never encountered Indians in my daily life. The prohibition dated from an 1891 statute, when the OFS was an independent Boer Republic, as explained here:

1891: The Statute Law of the Orange Free State prohibits "an Arab, a Chinaman, a Coolie or any other Asiatic or Coloured person from carrying on business or farming in the Orange Free State." All Indian businesses are forced to close by 11 September and owners deported from the Orange Free State without compensation

That statute was, and is an ugly stain on the history of the Orange Free State. However, the injustice led to an event that would ultimately have dramatic repercussions for system change in a different country, India.

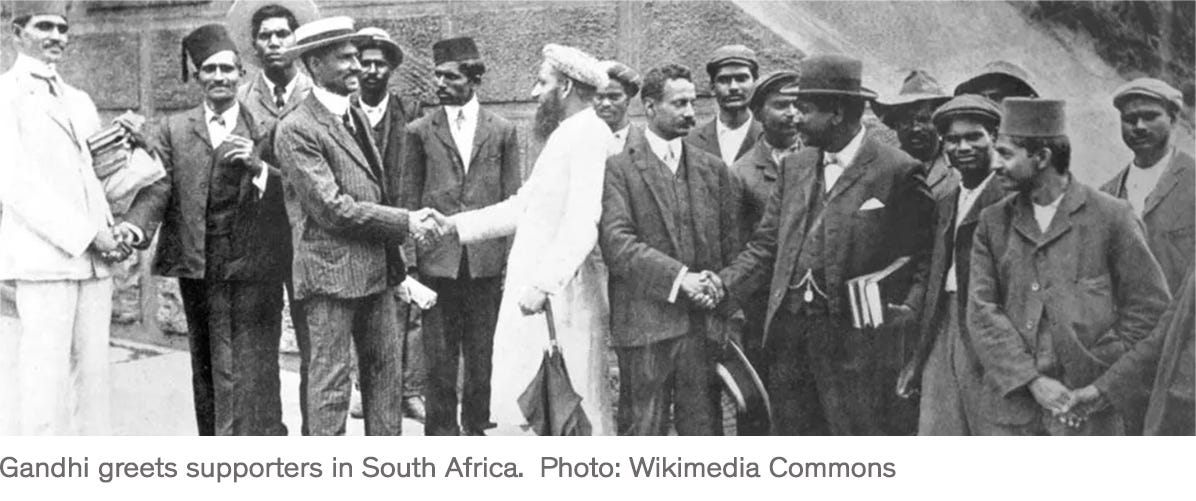

One day, Mohandas K. Gandhi, a young Indian lawyer working in South Africa, later to become the leader of the Indian National Congress, refused to comply with racial segregation rules on a South African train. As a result, he was forcibly ejected at Pietermaritzburg station. Gandhi later recalled that incident as his moment of truth. From thereon, he decided to fight injustice and defend his rights as an Indian by honing his skills in Satyagraha - a particular form of non-violent resistance.

Zeinab Badawi, Jubilee 2000 - and changing the IMF’s leadership.

The presence of Adam Habib at the SOAS event was meaningful, but if that was not enough to test my poise, there was Zeinab Badawi - and her critical role in helping Jubilee 2000 transform IMF policy on debt relief.

Twenty six years ago, in the summer of 1996, the Jubilee 2000 campaign, of which I was director, worked with Archbishop Basil Hume, the Catholic Archbishop of Britain, and the NGO CAFOD to organise an event with bishops from all over the world. The aim was that bishops would travel to Britain from all corners of the Catholic world, and testify to the harm caused to their people by the burden of debt owed to much richer creditor nations. They would give witness to economic failure and its impact - in the presence of one of the world’s most powerful creditors.

The IMF’s Damascene Conversion

We had also invited the Managing Director of the IMF, Michel Camdessus, a devout Catholic, and the IMF’s head of Policy Mr. Jack Boorman. The IMF was at that time the most intransigent public creditor blocking progress towards debt cancellation for thirty five of the world’s most indebted nations. IMF staff and the board of G8 finance ministers were ideologically opposed to suffering any losses from their institution’s often misguided lending to low income countries.

That meeting, and the testimonies of bishops, had an impact on Michel Camdessus, leading him to change his mind on the issue. He returned to Washington, persuaded the IMF board that debt relief was necessary; and instructed his staff, led by Jack Boorman, to begin negotiations on the Initiative for Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC).

The point of the story is this: that meeting - pivotal to the success of Jubilee 2000’s debt cancellation campaign - was chaired and presided over by none other than Ms Zeinab Badawi! At that time, Zeinab was a well known TV personality, but her importance to us was that she had been born in Africa, of Sudanese parents - and was, and is a brilliant moderator. It is fitting that she should now be the President of SOAS.

***

As I have had time this summer to gaze at the sea and reflect on these events, I am forced to conclude that Bobby Kennedy was right: “the winds of freedom and progress and justice have blown across the highest battlements” - of the South African state and the IMF - “have entered at every crevice” - including railway carriages - “and are carried by communications satellites and by the very air we breathe.”

Writing from Cape Town... it's good in these times to read a relatively optimistic perspective on our progress – thank you, Ann.

I admire Adam, but do wish he had pushed Wits to divest from fossil fuels before moving to SOAS.

As a SOAS student in the 1980s this story is particularly powerful. Connections across time, actions that reverberate and unknown futures. It's hard to be a campaigning human with no idea if your work will ever have results or meaning. Stories linking small actions and events are helpful to those of us still feeling like we are wading thorough treacle.