Will British/American/Australian/European house prices fall precipitously as a result of the rise in mortgage rates and cost-of-living crises?

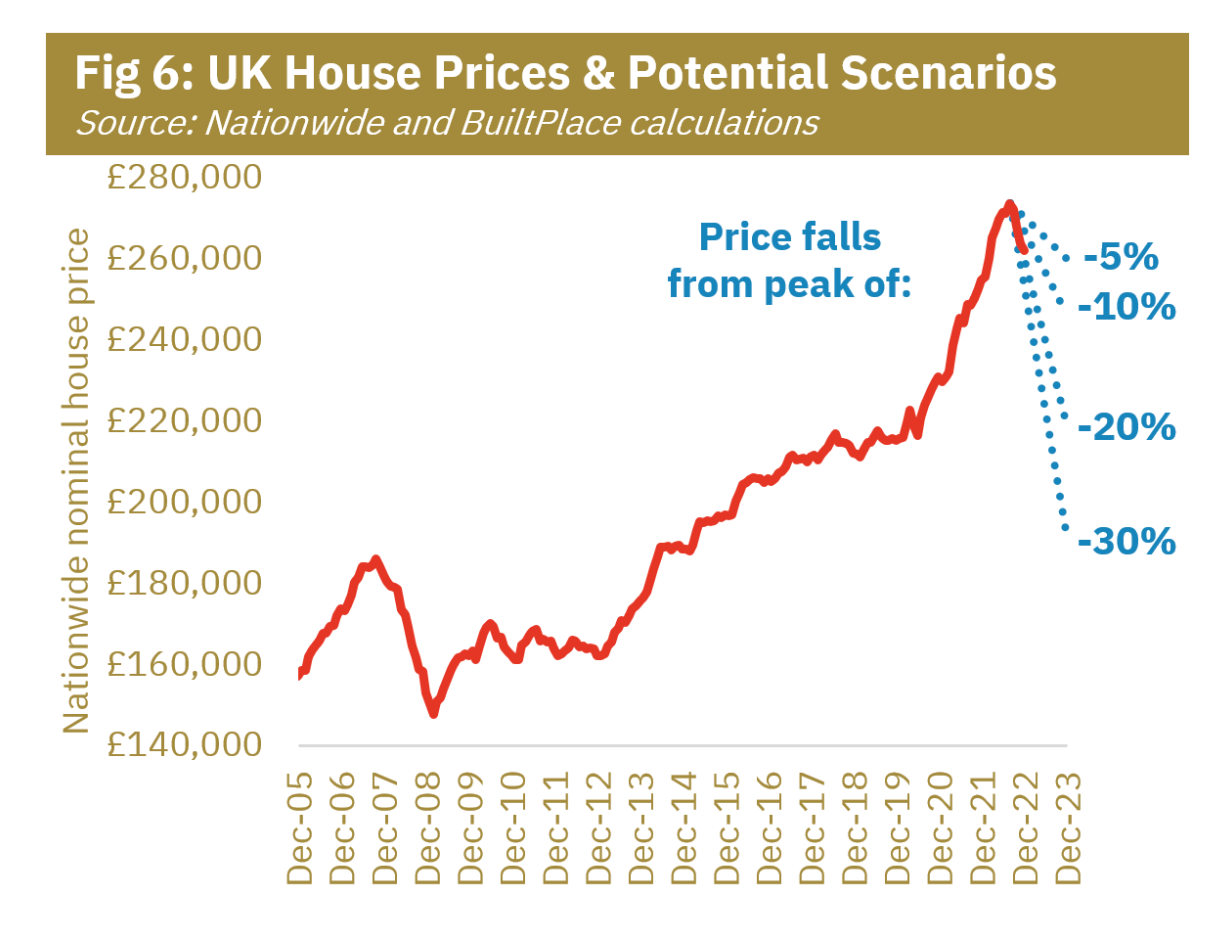

The chart below, dated 6th January, is from Neal Hudson, a respected British housing expert. He is hedging his bets.

I am not. I believe house prices will fall precipitously, not just because of higher mortgage payments in the US and elsewhere…

..but because higher central bank rates and tightening liquidity (fewer buyers) will accelerate the falls in asset prices already witnessed in 2022. (For examples see the demise of Bitcoin and the fall in Tesla shares.)

Globally house prices can be expected to follow suit.

As I wrote back in 2018: House prices have been blasted into the stratosphere, not by a shortage of supply, but by the excess of a potent propellant – finance.

To predict house price falls we need to lift our eyes from the micro, or the domestic economy, to the global macroeconomy.

As Josh Ryan-Collins and Laurie McFarlane argue in Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing – land is inelastic – a gift of nature.

It cannot be created and converted into capital. It cannot be produced or reproduced, or ‘used up.’ Above all, land (and property) is confined by boundaries. It cannot be moved out of Britain, China or Ireland.

The global supply of largely unregulated credit, by contrast, is elastic and with the help of global central banks and financial institutions, can be produced almost ad infinitum by both global but also national monetary and financial systems.

And unlike land, credit and capital are not confined by boundaries. In the 1960s and 70s, under pressure from Wall St. limits (frictions) on the movement of capital were removed. Today, in our globalized world, capital is highly mobile and its de-regulated flows unreliable and unstable.

The globalised concentration of property ownership, and the capital gains accruing to Wall St from such concentration, is a consequence of the current ‘billionaire’ global financial system - designed to suit the interests of the 1% - not the 99%.

Withdrawing the propellant of global finance

House prices began to fall when the propellant - finance or borrowed money - was withdrawn – or declined.

Globally, capital flows are in retreat. Not just because of central bank rate hikes and tightening liquidity, but also for political reasons. The Economist, in its latest issue, Globalisation, already slowing, is suffering a new assault - deplores this political (for which read ‘democratic’) ‘de-globalisation’ which restrains foreign investment and regulates investment.

Foreign direct investment has already fallen from a peak of 5.3% of global GDP in 2007 to 2.3% in 2021. The deals that continue to go ahead are more heavily regulated. In 2022 a Chinese buyer was permitted to acquire only 25% of a port in Hamburg, rather than the planned 35%. In 2021 half of all approvals of cross-border investment in France came with conditions attached.

Housing beyond the reach of the young

Sian Ní Mhuirí, 33 in the Financial Times’s recent deep dive into the Irish housing market is quoted as saying that

Housing has become a source of investment, speculation or retirement, not a basic human right.

This shift - from housing as a human right to property as primarily a financial asset regularly earning ‘rent’ in the form of interest, dividends, debt repayments, fees or capital gains - is a consequence of today’s system of globally mobile, largely unregulated rentier capitalism.

Consider one of Wall St.’s biggest private equity companies: Blackstone - also one of the biggest US property empires. The value of the company’s property holdings amount so they tell us, to $565 billion. As Fortune magazine notes, Blackstone’s empire extends well beyond US borders:

The Cosmopolitan and Bellagio hotels on the Las Vegas Strip. Stuyvesant Town, the largest apartment complex in Manhattan. Embassy Office Parks in Bangalore, one of India’s biggest destinations for IT tenants. Except for their prominence and enormous size, these properties don’t much resemble one another. They have something crucial in common, however: They’re all owned by investment funds controlled by Blackstone Group, the private equity giant.

Recently Blackstone suffered a setback to its expectation of millions of dollars in future rents from one of America’s biggest rental apartment complexes - Stuyvesant Town. That setback took the form of politics: democratic decision-making.

In 2018 Democrats won a majority in the New York state senate. A year later, writes Mark Vandevelde in the FT last Saturday, they reversed a ruling that would have ensured the expiration of regulated rents in the future. Instead they ruled that regulated rents

would stay on the books forever.

Microeconomic perspectives vs Macroeconomic perspectives

The economic consequence of throwing billions of dollars at scarce assets like property is predictable: price inflation. Asset price inflation that incidentally, unlike consumer price inflation, is tolerated and even encouraged by central bankers and orthodox economists.

Another consequence is the extraordinary rise in private and public debt - as Wall St and others based in the treasure houses of, for example, China, borrowed to invest in, or rather speculate in, property.

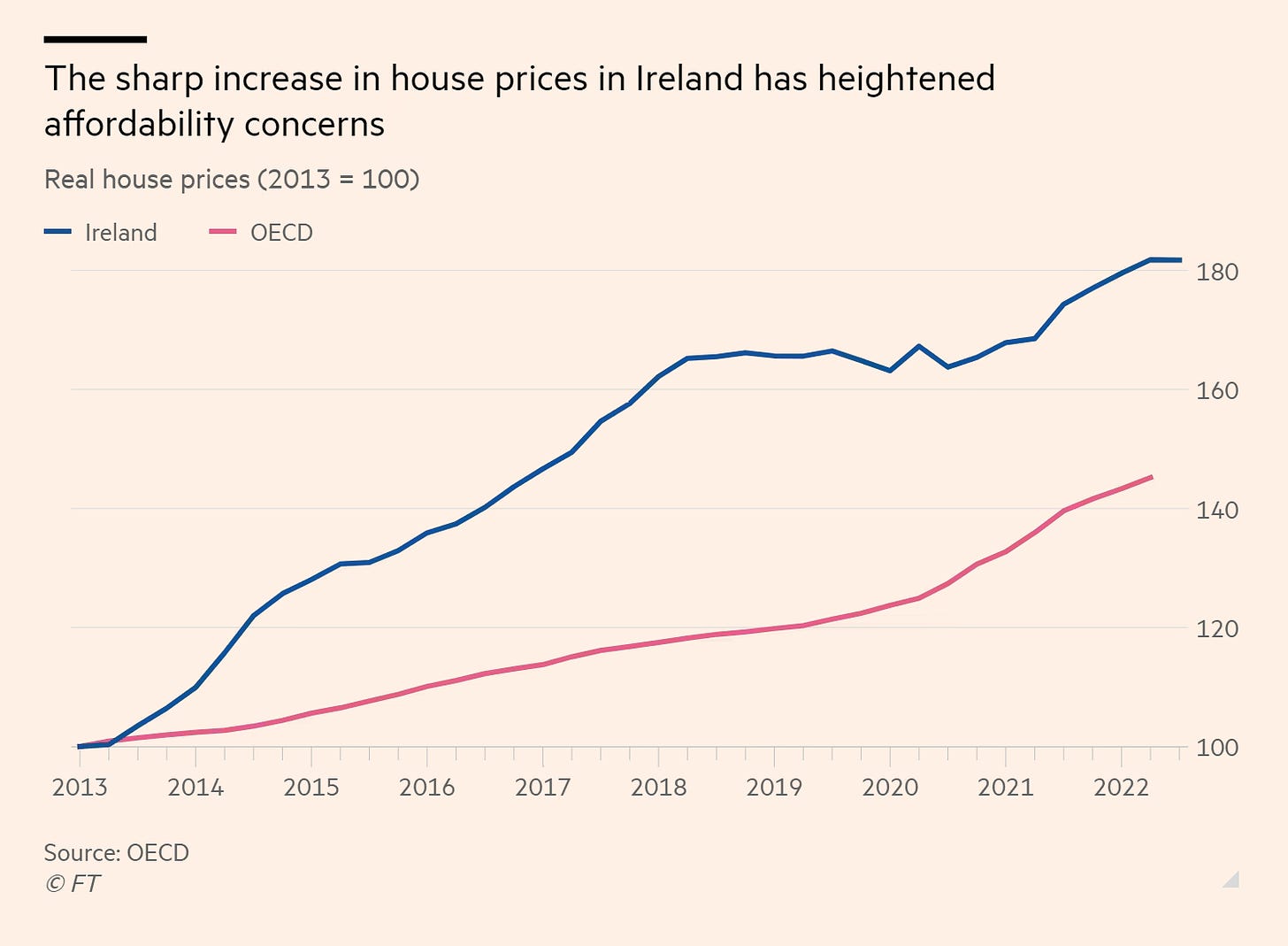

The impact of Wall St. and the global financial rentier system on home prices is felt keenly in Ireland - an open economy that, like Britain, is also a tax haven. In Ireland, as in many parts of Britain, housing is largely unaffordable, and homelessness rife. And, like Britain, rents in Ireland are largely deregulated. Hence the rise in rents, the decline in affordability, and, for Ireland, the emigration of thousands of young people - as the FT explained in December 2022:

nationwide rents rose by an average of 14.1 per cent in the third quarter this year compared with the same period in 2021…….the highest increase since it began tracking rents in 2005.….as many as seven out of 10 young people are considering moving abroad because they cannot afford somewhere to live — an embarrassing failure for one of the EU’s better-off nations.

The FT’s Jude Webber writing just after the Christmas break, informs us that:

According to official figures, Ireland had an unprecedented 11,397 people in emergency shelters in October, but experts say rough-sleepers, couch-surfers and other “hidden homeless” are not included, meaning the true problem is even greater.

In her piece Ms Webber cites Professor Ronan Lyons of Trinity College, Dublin. Like many mainstream economists, Prof. Lyons believes that higher prices are caused by a shortage of the supply of housing. The answer he believes is every developer’s wet dream: to spread more concrete across Ireland, and build more houses.

China took his advice and now has a massive oversupply of housing - financed by debt borrowed by private equity firms. As Isabel Hilton explains in the current issue of Prospect:

China had enough empty apartments to accommodate 90m people. In theory, the UK could house its entire population in China’s unused apartments and there would still be masses of room left over.

Like Wall St., China has its big private equity firms, the most notorious of which is Evergrande. According to Ms Hilton in Prospect:

By 2021, Evergrande, the world’s largest property company, was also its most leveraged, carrying a burden of $300bn in debt which, in a slowing market, investors increasingly doubted that it could pay. From Beijing’s perspective, Evergrande’s situation was more and more threatening: valued at $41bn in 2020, by the end of 2021 it was priced at less than $4bn and was struggling to meet scheduled interest payments on its dollar-denominated bonds.

It was not the only property company in trouble. In 2020, the government had tried to restrain the rapidly rising surplus of apartments by restricting the flow of finance to property firms. Now they were unable to service their existing debts or finance building new apartments for which, in many cases, prospective homeowners had already paid, or were committed to pay.

The microeconomics of ‘supply & demand’ vs the macroeconomics of globalisation

Back in June, 2018, in an article published in the Irish Times, I criticised Professor Ronan’s analysis of Ireland’s housing price rises, and his conclusion based on the theory of ‘supply and demand’:

repeated often by other professional economists, and echoed regularly by grateful developers and estate agents. But the ‘law’ of supply and demand is a micro-economic concept and applicable only to the ‘economy’ of individuals, households and firms.

As evidence of the flawed nature of this “fundamental” micro-economic theory, I present Ireland’s housing market in 2006 – the year in which the market boomed before imploding catastrophically.

Irish home construction peaked in that year. In a country of just 4 million people, more than 90,000 homes were built. And yet, despite this extraordinary increase in supply, and contrary to economic theory, prices in 2006 did not fall, but continued rising – by a whopping 11%.

To understand Ireland’s housing crisis, and to formulate sound policy to deal with it, requires a macro-economic approach.

To repeat: house prices have been blasted into the stratosphere, not because of a shortage of supply, but by the excess of a potent propellant – finance. House prices fall when the propellant is withdrawn – and flows of finance decline.

Hi Ann,

Do you know of any empirical analysis or modelling that tries to back out the financial component from the supply component? Seems to me both are real, though I appreciate the need for critical macro-financial arguments like yours to push back against simplistic and motivated supply-side reasoning.