The Sudden Paralysis of the System?

Messing with a Marvellously Intricate and Fragile Global System

It is hard to visualise the international financial system. Most of its activities are invisible and intangible.

I have tried to capture its fragility with this image of a remarkably complex, delicate and fragile cardboard structure – easily set ablaze, toppled or trampled on. [With acknowledgement to the artist, Daniel Agdag ]

The financial system of lending and borrowing, investing and speculating, making money from money – is a construction cobbled together by Wall St. effectively. It is largely bereft of democratic oversight or intervention.

As I write on Wednesday 28 September, 2022, the globalised system is dangerously unstable.

Central bankers and western politicians are messing with its marvellously intricate and fragile workings - governed only by the ‘invisible hand’ of markets. The thing could be toppled by the rash decisions of, for example far-right politicians like Britain’s ‘Kami-Kwasi Kwarteng’. His decision to casually chuck a grenade at the financial markets - via a ‘mini-Budget on Friday, 23 September - has caused a major wobble.

It can be set aflame by a terrorist attack on a European oil pipeline;

……by speculation; or crushed by the weight of excess debt. Or it can be de-stabilised by bad monetary policy decisions.

Today’s interventions

Globalisation/liberalisation dictates that democratic governments should not intervene in interest rate-setting. The market in money should be a ‘free market’. And in these markets the interests of creditors (investors, lenders) are to be paramount. Debtors have little or no power in global markets.

There is one exception to this rule: ‘independent’ central banks can intervene to fix the rates applied to financial institutions – banks, pension funds, hedge funds, private equity etc.

They should do so in the interests of the finance sector.

Today’s volatile and weakened currencies are in part the result of decisions taken by a relatively small group of unaccountable technocrats based in the Federal Reserve of the United States and the European Central Bank (ECB).

Central bank intervention in global capital markets

Central banks are public institutions backed by taxpayers and governed by civil servants, the the most senior of which – the governor – is appointed by politicians. Despite this public backing central bankers are governed by an economic ideology that requires them to be servants: not of the societies in which they are based, but of global capital markets.

The ideological basis of this orientation by central bankers to the interests of global finance is defined as ‘central bank independence’.

Before the current upheaval, the world’s central bankers had already reacted to a crisis caused by first, the Russian invasion and then speculative, and inflationary global markets in energy and food (see my earlier posts).

They did so by ‘tightening’.

One after another they intervened to hike interest rates in order to depress economic activity (employment, investment etc.) at home.

In other words, central bankers acted to deliberately intervene in markets and trigger recessions – in the hope that a collapse in domestic economic activity would lower the inflation of prices fixed in global largely deregulated and speculative Wall St. markets.

This obsession with inflation is because private creditors/financiers abhor inflation: it erodes the value of their most prized asset: debt (bonds, mortgages etc.)

Because a domestic response to a global phenomenon (energy price inflation) cannot be fixed by central bankers, markets in government and corporate bonds and stocks and shares, took fright. They all recognised higher rates would not reduce global prices in energy and food but instead would lead to recession at home.

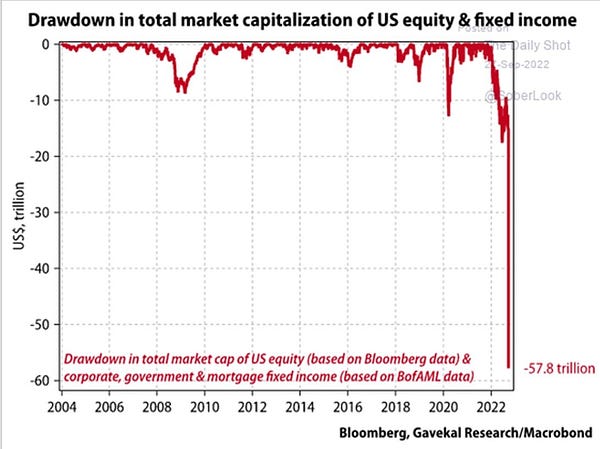

Quickly investors shored up their finances by selling bonds and stocks. Those markets started to fall.

Ignoring the impact on domestic economies, central bank technocrats hiked rates further and started selling bonds (quantitative tightening). In economic terms these actions are defined as “demand destruction”.

At this point Bloomberg took to calling central bank technocrats “the elephants in the room.”

The ECB recently ‘tightened’ monetary conditions by raising the three key ECB interest rates by 75 basis points - to 1.25%. That may not seem a lot but let me assure you in global money market terms those hikes are what Damon Runyon (in ‘Guys and Dolls’) called “big potatoes”.

The trouble is that the ECB has form.

In 2007 they hiked interest rates into the global financial crisis.

In June 2011 ECB central bankers hiked interest rates into the Eurozone crisis.

That was clumsy and economically brutal. What could possibly go wrong this time?

Right now, central bank elephants are trampling all over the livelihoods and lives of populations around the world - by intervening in (constricting) markets, raising rates, and destabilising the system.

The role of the ‘mighty dollar’

The system is dominated by the world’s reserve currency – the US dollar - issued by the world’s most powerful economic empire.

As a consequence of the US Federal Reserve’s decision to hike US rates, the dollar has strengthened. Capital was flushed out of emerging markets and funnelled into the US dollar. This has crushed the value of currencies around the world.

Energy used for transport (in countries without a sound public transport system) and pharmaceutical supplies (for COVID drugs etc) are all priced in dollars - so the cost of importing these essential goods has soared fuelling inflation at home.

So while Federal Reserve technocrats hiked rates to depress economic activity and lower inflation at home – they simultaneously exported inflation abroad.

Global economic warfare

But while these crises erupted worldwide, a far more worrying intervention in the global financial system occurred earlier, in February 2022.

The United States retaliated to the invasion of Ukraine by freezing Russia’s central bank reserves.

A week later, a meeting of G7 finance ministers went further: they agreed to intervene in the global market for oil, to impose a price cap on the market in Russian crude oil and petroleum products. The intent is to hit Moscow’s ability to finance the war in Ukraine.

They rallied enforcers.

“The provision of maritime transportation services, including insurance and finance, would be allowed only if the Russian oil cargoes are purchased at or below the price level……"determined by the broad coalition of countries adhering to and implementing the price cap".

But…..

Russia’s foreign reserves, like all national reserves, are a public good - the fruits of the work, economic activities and savings of the Russian people as a whole.

That was an act of economic aggression. Instead of cooling the crisis caused by Russia’s invasion - it forced the Russians into a corner - and intensified the crisis.

Financial globalisation and ‘the horns of a dilemma’

Writing in 1944, at the end of a catastrophic world war, Karl Polanyi – a political economist - sought to understand the economic and political forces that had led to the collapse of the international financial system in the 1920s and 30s; and to the rise of fascism.

He concluded that the fault lay in the separation of the world economy from society. A system that he regarded as unsustainable.

He called it “a utopia”.

“A society containing within its orbit a separate, self-regulating and autonomous economic sphere is a utopia.”

His point was that by separating the financial system from regulatory democracy (in short, politics) – the self-regulating international financial system was prone ultimately, to collapse.

Why “utopian”? We have had markets for more than 5,000 years if anthropologists are to be believed.

But those markets have always been integrated into society.

Back in the day the local chief/priest/headman determined whether the publican selling a pint of beer in the market was indeed selling a pint; whether a yard of cloth was truly a yard; and whether a pound of flesh was indeed a pound in weight.

Detach markets from such regulatory, political oversight by society – and all hell will break loose, was Polanyi’s point. Society would be cheated of pints of beer and yards of cloth, and mayhem would ensue. That’s why self-regulating or de-regulated markets are ‘utopian’.

Or as Polanyi put it more eloquently:

“A society containing within its orbit a separate, self-regulating and autonomous economic sphere is a utopia…… For the sake of society the market mechanism must be restricted. But this cannot be done without grave peril to economic life and therefore to society as a whole.”

Society would not, could not and did not stand for it. Why? Simply because an unregulated world market inflicts losses, unemployment, inflation, debt, low wages and instability on society.

The gold standard system in the 1920s caused so much mayhem in money, commodity and labour markets that governments, under pressure from society, were forced to intervene. They tried to regulate and stabilise the globalised but fragile system.

The more governments tried to intervene, the more likely their actions would pose a

“grave peril to economic life and therefore to society as a whole.”

And so it proved – in 1929.

The dilemma for today’s governments

To leave global markets to their own devices after Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, was, obviously, to invite trouble.

But on the other hand, to intervene in global markets risked, in Polanyi’s words “being caught on the horns of a dilemma”

“- either to continue on the paths of a utopia bound for destruction, or to halt on this path and risk the throwing out of gear of this marvellous but extremely artificial system.”

“A state of affairs was reached when a sudden paralysis of both the economic and the political institutions of society was well within the range of the possible. The need for re-integration of (economy and) society was apparent…”

Right now the international system shows every sign of “sudden paralysis”

Where do we go from here? Polanyi and the rise of authoritarianism

Polanyi argued that if democratic governments would not intervene in global markets to protect the interests of their citizens, then voters would turn to “strong men” (and women) for protection from global markets.

American society turned to Donald Trump in 2019 – for protection from markets in China and Mexico. In India they turned to President Modi. In China to President Xi. In Russia to President Putin.

Here in Britain voters in the election of a Prime Minister turned to the extreme right of the Tory party led first by the Brexiter, Boris Johnson (‘take back control”) and then ‘trickle down economics-with-tax-breaks-for-the-rich’, Liz Truss.

Liz Truss’s decisions soon after taking office, to sack the Permanent Secretary at the Treasury; and then to back the careless, casual, ill-thought-out mini-Budget of her Chancellor ‘Kami-Kwase’ Kwarteng, led on Wednesday the 28 September, to the sudden paralysis of the British financial system. The Bank of England was forced to intervene - and suddenly reversed a promise to sell UK gilts (debt) - a form of Quantitative Tightening - and instead began buying government debt (QE - or in some minds, the “monetisation of the government’s debt.”).

The Bank was obliged to do this because of the threatened imminent insolvency of pensions funds, who could not raise the cash to meet “margins” - their borrowing obligations.

That pressure was society effectively forcing an intervention in global markets - to protect the pensions of millions of British citizens.

Polanyi went on to argue that the sudden paralysis of the global economic system was a state of affairs out of which the fascist revolutions sprang.

Society had a choice: integration of the economy and society through political power on a democratic basis.

Or, if democracy proved too weak, integration on an authoritarian basis – and at the price of the sacrifice of democracy.

In today’s terms, Polanyi would have understood that “for the sake of society” (in this case Ukrainian, but also wider society) “the market mechanism (in money) must be restricted” – in our case, by the United States Treasury freezing Russian central bank reserves.

Today’s authoritarianism

Right wing extremists are in place today because democratic governments - or social democrats - failed to address the demand that citizens be protected from volatile, damaging global markets - by re-integrating those markets in society.

Instead, many social democratic governments preferred to defend and uphold the globalised, self-regulated economic system. The Clinton and Blair administrations were classic examples of social democracy acting in support of Wall St. effectively.

The consequence of that alignment between social democracy and global finance - is the decision by electorates to turn for protection to the many, by now well known far-right authoritarians in countries around the world. That phenomenon is now increasingly a feature of European politics. See the recent elections of the far-right in Sweden and Italy.

All of whom are contributing to a “sudden paralysis of the system.”

Ann this is so important at the moment - to se the links you set out - I wonder do you have anything we could publish as a blog for the Rapid Transition Alliance?

So helpful for non economists!

So terrifying that no lne seems to hear.