Hyperglobalisation, Big Government & Three Systemic Challenges

Trump’s chaotic plans to build a new world order

Machiavelli once wrote that

There is nothing more difficult to carry out, nor more doubtful of success, nor more dangerous to handle, than to initiate a new order of things.

President-elect Donald Trump gives every sign of ignoring that warning.

This is the first of three posts on the systemic challenges facing the world order as the Trump administration prepares to take its place in history. I focus on Big (US) Government’s determination to embark on a series of trade wars - with China, Mexico and Europe - and draw heavily on the work of Professor Michael Pettis, the economist, punk-music-club and record-club owner; but also the work of the early 20th century economist, John A. Hobson.

Global Trade and Big Government

Trumpians are trying to change the world order at a time of massive trade imbalances, obscene levels of inequality worldwide and general instability.

Unfettered ‘Free’ Trade Flows

These imbalances have arisen from both the preferences of the world’s wealthy, and from mainstream economists’s obsession with ‘free trade’ and the excessive importance attached to the export orientation of countries - with all countries expected to prioritise (through subsidies) their export sectors. Those policies have consequences: an excess of exports worldwide, resulting in over-production. Second, the transfer of wealth and investment away from domestic economies; and third, boosts to the income and profits of the wealthy, and of exporting corporations (think Apple, Pfizer and Cisco).

That obsession with exports and the simultaneous neglect of living standards in the domestic economy is most conspicuous in China and Germany.

As wealth is poured into the export sector, where it boosts the incomes of the already affluent - the wages/incomes of those active in the domestic economy - are repressed.1 Germany since the Hartz IV reforms is the classic example, but so is China. In both countries the export orientation has led to a rise in income inequality,2 and with it political tensions that have taken the form of ‘populism’.

In economies like those of China and Europe surpluses have built up - but also deficits in ‘consuming’ economies like the US and Britain.

But here’s the thing: the affluent don’t spend all they earn. There are limits to the number of properties, fashion items, yachts and foreign holidays they can buy.

In contrast, the 99% - the workers - spend all their income - on food, housing, healthcare and travel.

As earned incomes have fallen as a share of economies worldwide, the majority lack the purchasing power to buy all that is produced by the export-oriented economy. The consequence is over-production and under-consumption, the latter defined by economists as ‘weak demand’.

Far from society’s purchasing power chasing too few goods and services, we have too many goods and services chasing too little money/purchasing power/demand. China’s ‘ghost cities’ are an example of over-investment in assets that are beyond the reach of consumers.

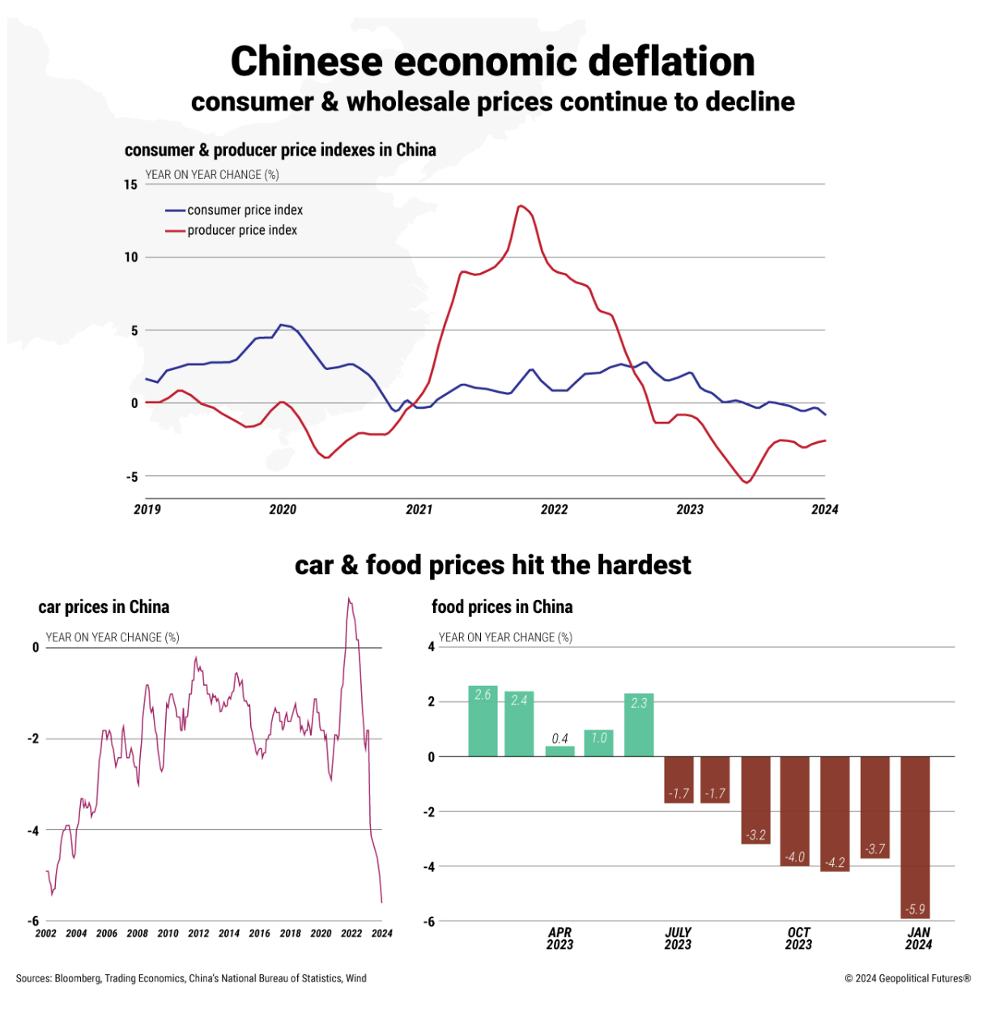

Weak demand for the over-production of goods and services leads to falling prices - deflation. 3

The problem is particularly acute in China, where the Communist government has shown itself completely unable to boost domestic demand - the (earned incomes) of the majority of the population - or, in other words, the consumption share of GDP - to absorb production. Even as the government continues to maintain economic activity the only way it knows how - by boosting domestic production - for export.

Unfettered Capital Flows, Donald Trump and Global Trade Distortions

The United States with its dedication to de-regulated open capital and trade accounts obliges China and exporters worldwide by accommodating trade and capital distortions. In other words, financial liberalisation means that the United States absorbs much of China’s trade surplus - as global consumer of last resort.

It does so, because as Pettis argues, since the 1970s the US has chosen for geopolitical and ideological reasons - reasoning promoted by the wealthy of Wall St - to eliminate most restrictions on its capital account, letting foreign investors have unfettered access to open US financial markets.4

The Challenge

If the US takes steps to reduce its own trade deficit (roughly half of global deficits) and no longer absorbs China’s surplus, China will have to dump its surplus elsewhere. That elsewhere is ‘the rest of the world’ a consequence that will be politically and economically unbearable for countries that choose, or are forced, to absorb the surplus.

The consequence of these likely actions by the Trump administration could therefore be disastrous. They could lead to a ‘Minsky Moment’ - in other words an unexpected ‘Moment’ of systemic collapse.

“Something has to break” writes Pettis “and I assume it will be the global trading system”

So triumphant Trumpians should beware Machiavelli’s advice:

there is nothing more difficult to carry out, nor more doubtful of success, nor more dangerous to handle, than to initiate a new order of things.

As always, thanks to all my subscribers - and please consider subscribing if you haven’t already.

My next post will review the systemic challenge posed by the instability of the global financial system, and the role of Big Government and Big (Central) Banks.

Capitalists that accumulate profits and capital gains prefer to transfer that wealth out of the country in which they are domiciled - and to invest their surplus in more profitable ventures in for example, low income countries. Exporting corporations prefer to invest their surpluses in more profitable ventures abroad. Apple, for example, prefers to invest in China's cheap labour than in the US rustbelt. This economic theory was developed by one John A. Hobson in the early 20th century, writing about South Africa. Cecil Rhodes had made a banking fortune in Britain, and instead of investing it at home, shifted it abroad and invested it in the largely undiscovered diamond and gold fields of SA where extraction could be undertaken by low-paid, unregulated black labour- and where much higher profits could be made than in Britain. Hobson’s book is called: Imperialism :A Study of the History, Politics and Economics of the Colonial Powers in Europe and America... Unfortunately, he was antisemitic, a real blot on his reputation.

Exporters also enjoy several taxpayer-financed privileges. See the US’s CHIPS Act, a $50bn package of subsidies and tax credits to lure chipmaking to America.

A capitalist company that builds say, armoured cars for export, has its profits boosted by government subsidies (issued by Export Credit Agencies like the US’s EXIM: “Helping American Business Win the Future”) Export Credit agencies also provide guarantees against losses if say, the dictator that is a beneficiary of the armoured cars, refuses to pay. For those in the domestic economy producing say, tomatoes, there are fewer, if any government subsidies and guarantees on the scale enjoyed by the export sector.

In aggregate terms those working in the German export sector have higher incomes than workers in the domestic economy, whose wages are restrained by the Hartz IV ‘Reforms’ (de-regulated labour, weakened unions etc.)

In the case of the UK, the deficit is balanced by capital inflows (buying up all valuable assets etc). If those flows into UK bonds, property and other assets (corporate and sovereign) were to reverse, sterling would lose value, and the British economy would be in dire straits... Wages and trades unions in the UK were steadily depressed by Thatcher’s labour market 'reforms’ of the 1980s and the massive defeat of the mineworkers strike by the full force of the British state. Above all, wages are depressed by globalisation - and competition from, for example, lower-paid Bangladeshi and Chinese workers...

Falling Chinese prices will arrive in UK and US markets (all other things being equal) - and cause other prices to fall.(Think inputs to car assembly etc.) Today's inflation is a result of supply bottlenecks (the pandemic), commodity market speculation; and QE 'too much money chasing too few goods'. The bottlenecks have ended. We now have the opposite of QE - Quantitative Tightening - where money is withdrawn from global capital markets, and cooling inflation. Unfortunately speculation in the global market for commodities continues.

When the Chinese sell goods and services they produce to Americans, they are paid in US dollars. Those profits and gains are promptly reinvested in US Treasury bills - because, unlike cash, bonds generate interest payments, and US bills are a safe asset. So nearly all of China's surplus income is funnelled into US capital markets, strengthening the US dollar. That may be good for Wall St... but not American workers.

NZ, being small, isolated, but also a well-developed Western economy, provides a stark example of where this ends up. We produce enough food to feed over 40 million people, but up to 1 in 3 (and growing!) children among our own 5 million population live in households experiencing inhumane hardship and malnutrition. Meanwhile, lobbying over the past decades has left us with the most expensive (and likely least-taxed) per-capita property market in the world, with the wealthy able to turn essential shelter into a dependable investment asset, on the back of low-productivity primary-good exports.

There is one reason why I include China in what I like to call the financial and industrial core, which is a better term than the global north and global south, which I just cringe it over at this point.

Because I think the real solution to the existential crisis being faced by all of humanity can only really be found at the local level; the calamity US plutocracy intends for the United States will simply push forward the changes we actually need to embrace.

Globalization is the biggest bubble ever conceived, localization is the necessary response. Every community has to engage in the significant creative challenge: figuring out how to live as comfortably as possible on the resources available within their own territory. And I do mean this at the local level, because this is where the energy intensity of the modern world is expended. It’s where the global supply chains originate and terminate, after passing through that financial and industrial core.

The carbon capture and the greatest energy efficiency is the stuff we never dig out of the ground, whether that’s fossil fuels or rare earth needed for renewables..

Walkable cities don’t need car infrastructure they don’t need the tarmac, they don’t need the parking space, they don’t need the tires or the gas or the car parts nor the car dealerships. Regional ecological restoration, and a vegetated urban landscape, passive building design, doesn’t need air conditioning or need to worry so much about extreme weather. And small scale multi farms, if managed in specific ways are 6 to 10 times more productive in total food per unit land than the large agricultural concerns of the global food processing sector. Economies of scale do not apply to agricultural productivity. This is because the productivity of the land is directly tied to the diversity of stuff growing in the land. A monoculture is antithetical to this biological reality. That holds true for agricultural productivity as much as it does for economic diversity. The global econony is a mono-culture of sustinance. It's a terrible survival strategy.