To Pay for Nurses' Wage Rises, Raise Incomes

Don't look at public sector pay through the wrong end of the economic telescope

Rishi Sunak and all the microeconomists that influence his government should finally begin to judge the question of public sector pay through a macroeconomic lens.

It’s really annoying to be re-visiting arguments we made at PRIME (Policy Research in Macroeconomics) throughout the 2010-2019 period. But until we finally dispense with the ideology that falling private and public wages are advantageous to the billionaire economy - re-visit we must. We have since 2010, spent time and energy rebutting arguments made by George Osborne and friends in the city, in economics and in the media - in favour of austerity.

Osborne’s strategy is now the Rishi Sunak strategy, and it is simple: divide the taxpaying public from those in the public sector - and rule. The strategy works by threatening the public with higher taxes if public sector pay and investment rises.

The strategy worked for Osborne. His government succeeded in destroying 1 million public sector jobs, cutting pay in the sector by nearly 6% while private sector pay rose: slashing funding for local authorities by nearly one third; and cutting by 27 per cent the number of older people receiving publicly funded social care.

Except, as we explained in The Economic Consequences of Mr Osborne:

vast damage [was] inflicted on public services and the public sector workforce. Five years of consolidation became ten years, with total spending cuts virtually doubling in size. The economy barely expanded in per capita terms relative to the pre-crisis peak, and public sector debt as a share of GDP was still rising in spite of a vast fire sale of public assets.

But enough of the past. Here follows the rebuttal for today’s version of the Osborne strategy. First, I want to re-assert this point: I am not in favour of public deficits and high levels of debt. It is economically healthy for the public finances to be in relative balance. Public sector deficits and debt are a function of economic failure: of a malfunctioning economy.

So Rishi Sunak’s government should fix the economy: ensure full, skilled and well-paid employment, and the debt will fall - as night follows day.

Let us begin the rebuttal with the BBC’s lunchtime news on 13 December - listened to by millions.

Ben Zaranko of the IFS was invited on and declared that to offer higher pay to nurses (something he agreed was necessary to retain essential workers) government:

“would have to provide more funding and that might require them to raise taxes.”

This trope “we can only afford to raise nurse’s pay if we make everyone else pay with higher taxes” is repeated endlessly by microeconomists of the IFS, by BBC journalists (with honourable exceptions) and by politicians.

Ever since 2010, we at PRIME have tried to explain that

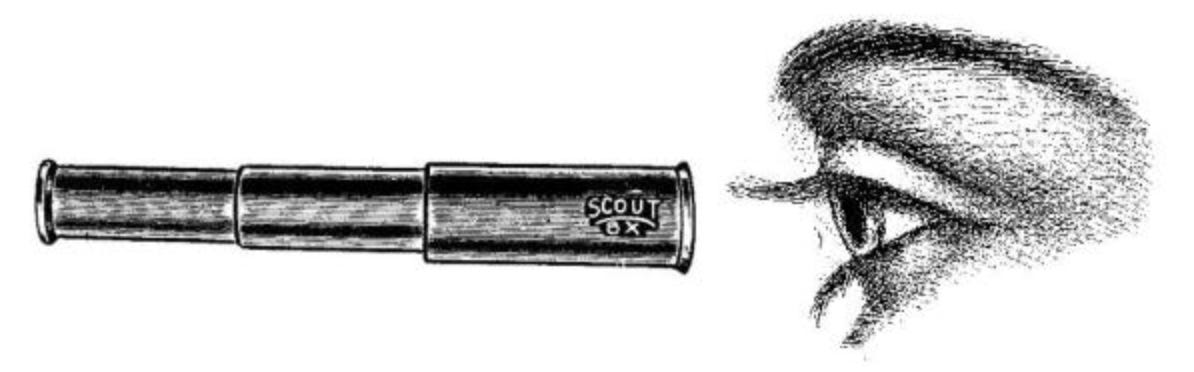

IFS staff consistently peer at the British economy through the wrong end of a telescope, distorting their analysis. In other words, they view the government’s budget in much the same way as a household might assess the impact of income and expenditure on a family’s budget.

But the government’s budget cannot be judged through a micro-economic lens.

The government does not raise finance from taxes

Instead the government raises finance by borrowing. [MMTers do not accept this point]

Then - and this is vital to understand - the government then spends that borrowed money into the economy. That spending is the thing that matters. By spending on higher pay or investment in infrastructure, the government automatically generates income (tax revenues) for the repayment of borrowing.

In other words, higher tax revenues are a consequence, not a source of government finance and spending.

The government is not a household. It does not wait until the end of the month or year to collect tax revenues - before it spends.

Instead it uses its great monetary powers to raise enormous amounts of finance - from financial institutions like pension funds.

The actual fund-raising is organised by the government’s Debt Management Office (DMO). As that department reported recently,

the government fully finances its projected financing requirement each year through the sale of debt. This is known as the ‘full funding rule’. The government therefore issues sufficient wholesale and retail debt instruments, through gilts, Treasury bills (for debt financing purposes), and NS&I products, so as to enable it to meet its projected financing requirement in full.

When that finance is raised, if invested in people and infrastructure (like hospitals, railways or universities) spending will generate income in the form of tax revenues for the government. This is because the individuals, households and firms that are beneficiaries of that spending, pay taxes on their income, profits and capital gains - via PAYE and other means of tax collection.

Importantly, they only pay taxes after they have earned income - at the end of the week, month or year.

Once earned, individuals, households and firms spend and invest their new, higher income. They spend on goods, on rent, on food, and on services provided by for example, football clubs, lawyers, accountants, musicians, artists etc. That spending generates additional tax revenues for government, this time paid by football clubs, firms, shops, landlords, farmers, lawyers, musicians etc.

And these taxpayers don’t just pay once; they continue paying taxes for months and even years after receiving a pay rise or government contract.

In other words, tax revenues are multiplied for government by its investment or spending on higher incomes and infrastructure.

There is no need to raise taxes to fund spending.

The real need is to raise incomes - because higher incomes for individuals, households and firms generates higher income for the government.

Government financing mechanisms

The government can raise the initial financing needed to spend on say, higher wages for nurses, because, unlike private households or shops or firms, it has guaranteed future income with which to repay its borrowing.

In the UK about 32 million individuals are obliged by law to pay taxes either on their wages, salaries or fees. Millions of traders are obliged to pay corporation or capital gains taxes on their profits and capital gains. In addition many traders, households and individuals pay VAT, Insurance Premium Tax, Air Passenger Duty, Landfill Tax, Climate Change levy etc..

And these taxes are due not just in the coming year, but for many decades - even centuries - into the future.

No household or company is guaranteed income decades into the future!

That is why government borrowing is so attractive to lenders. And it is why government finances must be treated from a macroeconomic, not microeconomic perspective. 1

How government borrowing helps pay for future pensions

On the 13th December. the UK government raised £3 billion from a 10-year gilt issue, and promised to pay just 1% to those individuals and institutions that lent it money.

Because government borrowing is so safe, lenders clamoured to buy the asset that is a UK government loan, or gilt - even though they were due to earn only 1% from their loan. Twice as many bid to buy the debt than were successful in acquiring gilts.

Many of those lenders would have been pension funds, seeking the safest place to invest the pension savings of British citizens - in order to protect the income needed to pay future pensioners in retirement. Think of that borrowing by government and lending by pension funds as at the heart of the ‘plumbing’ of the British monetary system.

Government borrowing helps pay and maintain the value of future pensions.

So government borrowing does citizens a great service twice over. It could pay for higher wages for nurses, railway workers, teachers and other public sector workers (and that would generate income for shopkeepers, farmers, musicians etc.) AND it could help finance and protect future pensions for nurses, teachers and other public and private sector workers.

Raising incomes would fix the government’s deficit

Now as readers will know, public and private sector pay has been falling as a share of the nation’s income for many years now. We are in the fourteenth year of a pay crisis, intensified over 2021 and 2022 by sharply rising inflation.

According to Martin Wolf in the Financial Times:

Since the Conservatives won power in May 2010, overall real average pay (including bonuses) had risen by 5.5 per cent in the private sector by September 2022, but fallen by 5.9 per cent in the public sector. Startlingly, between January 2021 and September 2022, average real pay in the private sector fell by 1.5 per cent, but in the public sector pay fell by 7.7 per cent. In fact, all the decline in real public sector pay since 2010 has occurred in the past two years

[Ignore the rest of Wolf’s case. He too looks at the public finances through the wrong end of an economic telescope: “Taxes could be raised if the will were there.”]

Because of cuts in the incomes of both private and public sector workers, tax revenues have fallen and government deficits and public debt has risen.

Over 2010-2019, when austerity based on cuts in government spending on the public sector took hold under George Osborne, the public debt ratio increased by 22 percentage point of GDP – the worst performance over a decade of economic recovery for a century (here).

Falls in the nation’s incomes lead to falls in government tax revenues - as night follows day.

Rises in national incomes will lead to a rise in government revenues - and a fall in public deficits and debt.

As night follows day.

Keynes was right when he argued in a 1931 BBC radio broadcast (published as “Keynes on the Wireless”) that:

You cannot balance the nation’s books by cutting the nation’s income

Rishi Sunak’s new fledgling government could balance the nation’s books and increase tax revenues by agreeing to union demands to raise public sector workers’ income - in real terms, relative to inflation.

He - and all the microeconomists that influence his government - should finally begin to judge the question of public sector pay through the macroeconomic end of the telescope.

Microeconomists concentrate on economics at the micro level - that of the individual, household or firm. Macroeconomists focus on aggregate economic activity across sectors, across the whole economy and across the international economy.

Why doesn’t the Labour Party argue its case from the macro economic perspective? If they don’t, who will? Ian

If taxes don’t fund government spending but borrowing does, can you explain what is the difference between money used to pay taxes and money borrowed? And where does the private sector find, say, £120bn as it did during one quarter of 2020? And can you show us the accounting model you use to substantiate this claim, and the MMT model which (I have to assume you have found) which rejects this?