On New Year’s Eve I was at a neighbour’s party packed with artists. Pretty soon the discussion turned to the state of the art market. While I had watched booming sales of art works over the years - and the debt leveraged against them - I had taken my eye off the art market ball. So the news that it had fallen “widely flat against expectations” in 2023, and is likely facing an even deeper correction, came as a surprise. After all, the post-pandemic wealth of the very rich had spiralled, and become even more concentrated. So why had they not continued to splash out on works of art? Why had the art market moved from “herd mentality to selectivity, from bloat to sobriety” as Katya Kazakina reports? Why the growing fear

… about gallery closings and collectors dumping art. Younger dealers, who’ve never lived through a market hiccup, lament the drop in Instagram sales. Investors bristle at unsatisfactory returns on art assets.

The answer, I suggest, is that after the GFC many art purchases were financed by ‘easy money’, borrowed at low rates of interest, with few questions asked, and courtesy of central bankers and ‘Quantitative Easing’. Those same central bank governors then took the punch bowl away by ratcheting up rates at reckless speed.

I dived into various art market sites to get a sense of the scale of the fall in prices and landed on Artsy…

In 2023, the most expensive artworks at auction paled in comparison to last year. The top 100 lots at auction this year totaled $2.4 billion, compared to $4.1 billion in 2022. This steep decline was evident from midway through the year, when combined sales across Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips saw an 18% decline for the first half of 2023, according to ArtTactic, through to the fall auction season in New York, which fell widely flat against expectations.

Deflating assets

The art market is no different from other deflating asset markets. Its prices are deflating as buyers struggle with rising rates, and prioritise the repayment of outstanding debts over new purchases and borrowing. Back in early November I had warned in this substack post

that the era of booming debt inflation is now turning into a spiral of rapid debt deflation. Debts are being paid down, written off, or defaulted on - and borrowing, including mortgage borrowing, is in decline. We are heading for a period of disinflation - dangerous for millions of heavily indebted borrowers.

Why? Because deflation erodes the value (price) of assets, but increases the value of debt relative to assets. Debtors lose and creditors gain - to put it crudely, and as explained in an earlier post.

And then on the 8 January, Adam Tooze drew our attention to this chart - which shows EU loan demand “cratering” - worse than in the Eurozone crisis - and asks why we’re not panicking?

The inflation debate

Debt deflation, triggered by high real rates of interest and low, real wages worldwide, drives the fall in prices of goods and services - and assets - by lowering demand for those goods and assets.

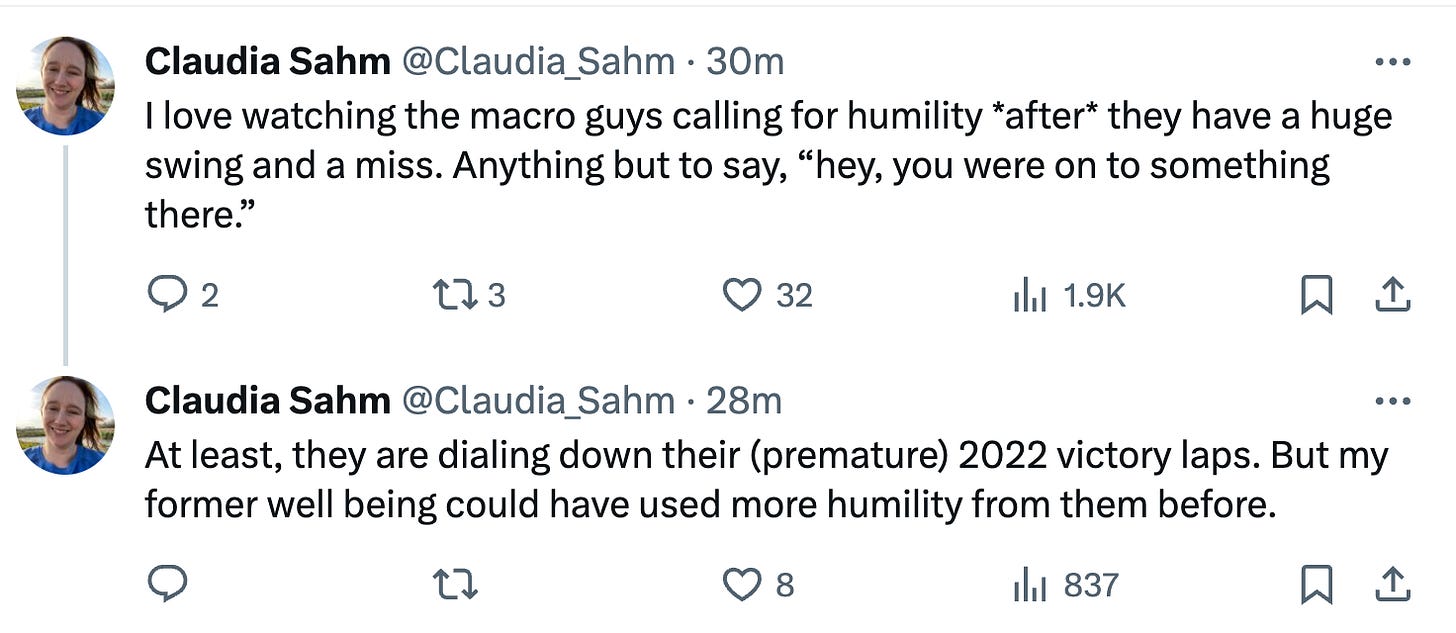

Falling inflation has led some members of the economics profession to celebrate: those who warned that inflation was ‘transitory’. and down to energy supply shocks and transport choke-points after the pandemic. Most prominent of the ‘transitory’ team is one I admire, the ex-Federal Reserve economist, Claudia Sahm.

Others, including the ever-certain but usually-wrong member of the deregulatory cabal that delivered the GFC - Larry Summers - warned that inflation could not and would not be tamed without a dramatic rise in US unemployment. Wall St.’s favourite economist implied - no demanded - higher unemployment as the means to lower wages, and dampen inflation.

“We need five years of unemployment above 5% to contain inflation — in other words, we need two years of 7.5% unemployment or five years of 6% unemployment or one year of 10% unemployment,” Summers said Monday during a speech in London, according to Bloomberg. “There are numbers that are remarkably discouraging relative to the Fed Reserve view.”

Like the governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, who called for wage restraint, Summers was mistaken yet again - both in moral and economic terms. Nevertheless as inflation falls against both their expectations, he and other class warriors remain unrepentant, as Claudia noted in this tweet:

While the ‘transitory’ team were more sensible than the right-wing economists around Larry Summers, I dare to stick my neck out and argue: both are wrong to think inflation will settle down at 2%.

Why? Because of what is happening in China.

China is in a debt-deflationary trap

China is enduring a sustained decrease in the prices of assets, goods and services. Falling consumer prices may be good for Chinese shoppers, but falling asset prices are bad for Chinese artists, homeowners, property developers - and debtors. Its also bad for the rest of the world, as China’s major exports fall in price, and deflation is exported abroad.

For example, transaction prices for hot-rolled coils of thin steel sheets, including freight charges, fell 14% in East Asia from the most recent highs in March. Steel products overall dropped 40% as stockpiles in China were sent overseas, pushing down prices in Asia.

China is a low-wage economy that since 1998 has enjoyed a massive property boom. The boom was largely due to a) the financialisation/globalisation of the Chinese economy and b) demand for homes by workers moving from rural areas into the big cities, and getting rich quick as property values inflated - effortlessly.

Like Australians, many Chinese are obsessed with property because of the vast wealth they have made in the past as prices surged. Tiny apartments in cities such as Shanghai were suddenly worth as much as those in Sydney, London or New York despite average wages in the cities being well below those in more developed countries.

The boom also enriched local governments, whose revenues were boosted by land sales to big developers.

Invariably the process has gone into reverse. Chinese wages could not keep up with the rising cost of debts and borrowing, and wages are still falling as this recent Bloomberg post shows, so demand for housing is falling.

Why does China matter? Because its $18 trillion economy - the world’s second largest - amounts to almost 20 per cent of global income and more than 30% of global manufacturing. When China sneezes… the world catches cold.

To avoid China - and the world - plunging into a debt-deflationary trap would require the Communist party of China to introduce policies that would a) raise Chinese wages and living standards, b) extend welfare provision, c) write-off unpayable private and public debts - and d) re-focus its economy away from its global orientation and towards the domestic economy. Instead of serving the interests of big corporations like Apple and other Wall St. beneficiaries, the Chinese government would instead move back towards serving the interests of the population as a whole.

In other words, to avoid another deflationary crash would require the Chinese government to lead a revolution in economic policy-making.

Such an outcome is unlikely for several reasons. First, it would challenge the interests of powerful Chinese elites and corporations engaged in the export sector.

Second, it would raise costs for those big companies in the West dependent on China’s cheap labour for their immense profits (think Apple) and capital gains (think Blackrock). Their governments will fight back with protectionist policies triggering more intensive trade wars.

Third China (and the OECD) would have to overcome the economic and entrenched ideology of exponential ‘growth’ - central to the financialisation and globalisation of the world economy - as my colleague Geoff Tily argued in this highly recommended article on PRIME’s website: On Prosperity, Growth and Finance.

So hang on to your hats. Instead of a revolution in economic theory, we’re in for ‘higher for longer’ interest rates; another deflationary era … and more crashing asset markets.

Doesn't ‘higher for longer’ interest rates and another deflationary era kind contradictroy a little ? IF deflation is the trend, the fed doesn't need to higher for longer right? Also the US gov deficit spending and fiscal expansion seems keep fueling the inflation problem so the rate won't come down?