Why are rents rising at record rates?

On the perverse impact of debt deflation after a period of debt inflation

Rents are rising even while there is distress selling in the British housing market. The British National Residential Landlords Association says a record number of buy-to-let investors are planning to sell. Something similar appears to be happening in the US Commercial Real Estate market where both transactions and prices are down. And then there is the collapse of China’s biggest real estate company, Evergrande.

Renters are having a hard time not just here in London, but worldwide. There is alarm amongst buy-to-let owners and debtors everywhere.

High real interest rates help explain why buy-to-let investors made up only 8.1% of the UK market this last quarter – 40% less than the same quarter last year. And, according to Hamptons, in a report titled, Why Rents are Set to Grow Four Times Faster than House Prices, there are signs that existing landlords are steadily reducing their borrowing, with UK Finance reporting a 30,000 fall this year in the number of outstanding buy-to-let mortgages.

Central bankers, having for long tolerated debt inflation, have dramatically (and in my view mistakenly) raised interest rates. They are now indicating that rates are set to stay higher for longer. Higher rates have forced landlords (and other debtors) with high debt to income ratios to sell up to raise the cash to pay down increasingly costly debts. The resulting shrinkage of available properties explain why rentals are rising at one of the fastest rates on record in London, up 30% since the pandemic, and 12% year on year in August.

Higher rates and forced sales helps explain why inflation is falling - as central bankers intended - not just in the UK, but in the Eurozone where the FT reports today that inflation has fallen to its lowest level for almost two years.

Why have central banks hiked rates?

Central bank action needs to be understood in a broader context. Since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) central bank technocrats and other policy makers have sat on the sidelines as debt inflation took hold. In other words, they did little to stem the availability of ‘easy money’ or credit for borrowers. The de-regulation of credit creation by main street and ‘shadow’ bankers meant that lenders could spray money around, and many borrowers were not checked for their ‘credibility’ - or ability to repay - in taking on more debt.

This easy availability of money - presided over by the ‘guardians of the nation’s finances’ - inflated the value of all assets including property. And while central bankers turned a blind eye to the inflation of both debt and assets owned or sold by the rich - they remained rigidly opposed to consumer inflation - which erodes the value of debt and hurts creditors and other lenders.

While presiding over debt inflation central bankers kept interest rates very low - even negative - for nearly ten years after the GFC. The purpose as Carolyn Sissoko has argued, was to rescue the leveraged debt markets (i.e. ‘private equity’, hedge funds etc.) from the crazy borrowing and reckless investments they had made prior to the GFC. Low rates made it easier to refinance the debt while Quantitative Easing made it possible to raise even more finance almost effortlessly.

The initial policy of low interest rates “for an extended period” that the US Federal Reserve adopted in March 2009 was designed to address weaknesses in credit markets and to make it easier to refinance debt, both mortgages and corporate debt (FOMC 2009). It was accompanied by an increase in quantitative easing to support the mortgage market.

…..Needless to say, this policy was extremely important to the ease with which both leveraged loans and junk bonds were refinanced. 1

Low rates were an incentive for corporates and leveraged buyout funds to keep up the debt bubble, by going on yet another wild borrowing spree.

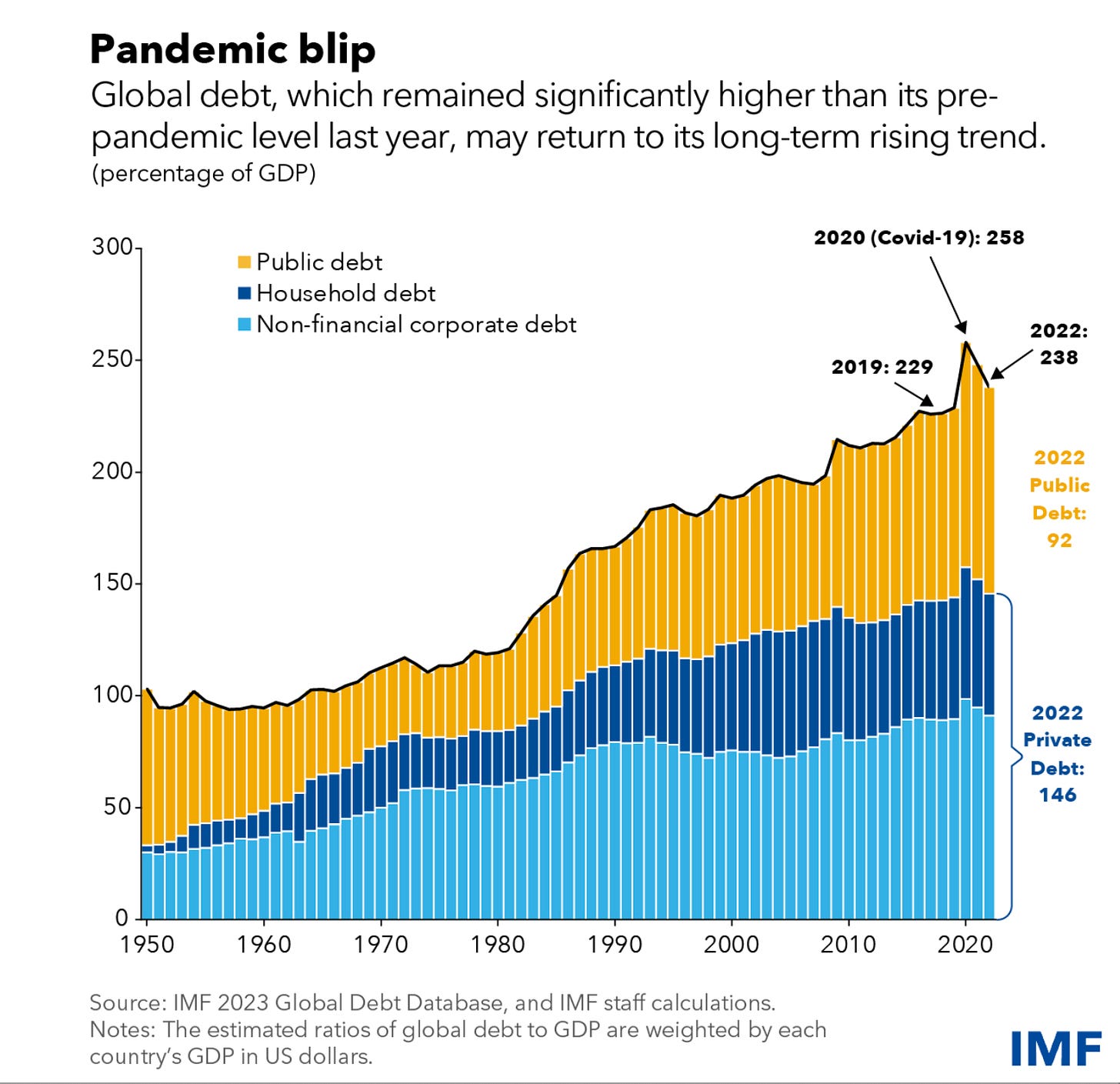

Hence the spike in the debt to global income ratio of 2015. (See chart below)

That borrowing spree peaked in the lead up to the COVID pandemic and resulted in the March, 2020 shadow banking crash - forgotten by most commentators. That in turn led to a GFC-comparable bailout by central bankers. As the New York Times reported:

the 2020 meltdown echoed the 2008 crisis in seriousness and complexity. Where the housing crisis and ensuing crash took years to unfold, the coronavirus panic had struck in weeks.

As March wore on, each hour incubating a new calamity, policymakers were forced to cross boundaries, break precedents and make new uses of the U.S. government’s vast powers to save domestic markets, keep cash flowing abroad and prevent a full-blown financial crisis from compounding a public health tragedy.

Since the pandemic, while the ratio of debt to global income is still very high, it is now falling, as the IMF chart (below) shows.

As has recurred with painful frequency over the last fifty years, after the debt inflation of the post-GFC era, we may now be entering yet another era of debt-deflation.

And debt deflationary forces are dangerous and are to be feared - especially by debtors.

Why Debt Inflation leads to Debt Deflation - and recurring financial crises

The cycle of debt inflation followed by debt deflation has been an endless one since the era of financial deregulation began in the late 1960s and early 1970s - prior to the Thatcher/Reagan transformation of the global economy.

The world’s periodic financial crises can be explained by this phenomenon.

I gave a talk on this subject at the excellent Flipside Festival in the hamlet of Sweffling, Suffolk last Saturday. They had asked for a discussion of my book The Case for the Green New Deal, in which I make a link between excessive credit creation and rising levels of extraction, production and consumption…

In preparation for the talk I looked up the ratio of current levels of credit/debt (both public and and private) to global income (GDP).

It is not a pretty sight.

In 2007 – when the global debt bubble burst and unleashed a global economic catastrophe – global debt was 269% of global income. Regrettably the GFC was not catastrophic enough to persuade regulators – politicians, economists and central bankers - to manage, regulate and stabilise the system of globalised credit creation, generated in large part by the shadow banking system.

In other words, the existing de-regulated financial system was not fixed. Instead it was consolidated.

The result is reflected in the above chart - a continuing, and ever-expanding bubble, since the GFC. of credit/debt relative to global income.

By 2015 debt had risen to a massive 286% of global GDP.

Today, global debt has gone into reverse. It has fallen to just 238% of GDP – you can see the 2022 downwards blip in the chart above.

That fall in overall debt ought in common sense terms, to be good news. Sadly, it is not. Instead, it is an expression of the crisis in rental properties: borrowers are selling up to raise the cash to pay off debts. Others are staying away from credit markets. Rates are too high, and borrowing too risky. As a result, the amount of debt in the economy is falling.

The debt inflation is going into reverse. A debt deflation is beginning to take hold.

In the past, debt deflations have led to Great Depressions.

Predicting the ‘when’ of financial crises

Twenty years ago, back in 2003, and thanks to what I learnt from economists like Dr. Geoff Tily, I began to make the argument that debt inflations and debt deflations were both typical of globally deregulated finance, but also causal of global financial crises.

I and my colleagues were pretty much laughed out of court.

Since then we have endured two grave global financial crises (2007-9 and March 2020) and appear to be embarked on a third.

In that year I edited a book published by the New Economics Foundation: The Real World Economic Outlook. Its purpose was to challenge the IMF’s complacent World Economic Outlook which in 2003 was weirdly upbeat about global economic prospects. As I explained in the book’s introduction:

On the worrying threat of deflation, about which many economists are now expressing grave concerns, IMF staff, obsessed by inflation over these last 30 years, shrugged off the risks, and [in their 2003 report)] wrote:

“The risk of a generalized global deflation, or even of a deflationary spiral in the major economies, appears small: financial markets and institutions have remained broadly resilient so far: corporate and household debt burdens appear manageable; and there remains scope for policy adjustment in most countries.” [i]

To promote the book I wrote a piece for Open Democracy published on 31st August, 2003 and titled: The Coming First World Debt Crisis.

The report predicts that a giant credit bubble, created by central bankers and finance ministers (the engineers of decades of easy money) has now reached a tipping point. This point at which the bubble of financial assets exceeds GDP by nine times has triggered financial crisis elsewhere. Another tipping point would be a rise in interest rates not unlikely for economies like the US and UK which have massive foreign deficits.

My timing was a little too early. It took a further expansion of the credit bubble - or debt inflation - and four more years of speculation before the system blew up in August, 2007. Subsequently my reputation as a predictor of the GFC soared.

This time I may be early again in the timing of a new debt deflationary implosion. But the 1930s economist Irving Fisher had taught me, and many others, to be alert to the signs.

Irving Fisher explains the perversity of debt deflation

Irving Fisher is famous for his Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions – a paper that helped resurrect his reputation, when, like the IMF in 2003 he made a quite disastrous prediction of the state of the NY stock market. Not that he was alone. His analysis of the debt inflation era that preceded the Great Depression, conformed to the economic orthodoxy of those days - an orthodoxy still dominant today.

On 9 September 1929, Fisher warned that

There may be a recession in stock prices, but not anything in the nature of a crash. 2

Then as debt inflation peaked, and Wall St., and the financial system were set to implode, Fisher pronounced optimistically that,

Stock prices had reached a permanently high plateau. 3

That euphoric forecast on the very eve of the financial cataclysm of October 1929 cost him dear. He lost a personal fortune of between $6 and $10 million which as JK Galbraith noted in his book, The Great Crash.

….was a sizable sum, even for an economics professor.

Fisher, suitably humbled, learned the lesson handed out by the 1929 Crash and began to rebuild his reputation with The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions.

Today’s parallels

Readers may well ask why that paper is relevant now? The answer is simply that conditions today are similar to those leading to the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Since the GFC and again since the pandemic, there’s been a continuing debt inflation - a veritable boom in debt or credit issuance. As noted above, this inflation was largely fueled by obliging central bankers that dogmatically refused to regulate the sector, and that kept interest rates low for almost ten years after the GFC to help creditor institutions (if not sub-prime homeowners) recover.

Fisher explained today’s alarms succinctly:

a state of over-indebtedness exists… this will tend to lead to liquidation through the alarm of debtors or creditors or both…

The state of over-indebtedness and associated alarms (i.e. hikes in interest rates) leads to a “chain of consequences” that have nine links.

(1) The first is debt liquidation that leads to distress-selling

In other words, to afford the higher rates, sellers are forced to make a sale and to cut prices.

That, Fisher contends, leads to the second “consequence”

(2) Contraction of deposit currency, as bank loans are paid off, and to a slowing down of velocity of circulation.

There is less borrowing as a result of ‘alarms’; less money in the bank, less circulating in the economy (purses have been snapped shut); and less money to be made from lending.

Right on cue, in an article by Max Reyes on 26 September 2023, Bloomberg reported the following::

The US banking industry’s total deposits declined year-over-year for the first time in data going back to 1994 following a tumultuous period for the banking sector.

This contraction of deposit currency, argued Irving Fisher, triggers

(3) A fall in the level of prices.

Again, readers may think of a ‘fall in the level of prices’ as a good thing. The Bank of England explains why such falls occur, and why it is bad for business:

What would you do if you knew the £100 bike you wanted to buy today, was going to be reduced to £90 tomorrow? You would probably wait to buy it for the cheaper price. When prices begin to fall, people expect they will continue to go down. This expectation results in people spending less today, in hope of buying at a cheaper price tomorrow. This is bad for businesses.

That fall in business sales is Fisher’s next “consequence”:

(4) A still greater fall in the net worth of businesses, precipitating bankruptcies.

And

(5) A like fall in profits, which in a …private-profit society, leads concerns which are running at a loss, to make

(6) A reduction in output, in trade and in the employment of labor.

In other words, when prices and sales fall, firms freeze activity, or unfortunately go bust…and lay off workers.

These losses, bankruptcies and unemployment lead to the next consequence:

(7) Pessimism and loss of confidence, which in turn lead to

(8) Hoarding and slowing down still more the velocity of circulation.

“The above eight changes” argued Fisher, cause

(9) Complicated disturbances in the rate of interest, in particular, a fall in the nominal, or money, rates and a rise in the real, or commodity rates of interest.

A quick explainer: Complicated disturbances in the rate of interest

Why does a fall in prices raise borrowing costs in real terms? Once again, those clever economists at the Bank of England explain the phenomenon concisely:

If you borrow £100 to buy your bike today but prices fall, you will still owe £100 tomorrow.

You could not sell the bike for the full amount needed to repay the debt, as its value has fallen to £90. But your debt keeps its value.

Now say you bought a house and its value dropped by £10,000, but you are still paying off the mortgage. Even though the house isn’t worth its original value, you still have to pay the same amount.

In other words, the mortgage (debt) increases in cost and value, just as - or relative to - the falling value of the house.

If the borrower loses her job and can’t afford to pay the interest on the mortgage, the borrower becomes a forced seller. This means selling the house at a price that enables her to pay off the mortgage. If the price falls below that level, trouble ensues.

That is why debt deflation is so wicked in its impact - it raises the cost of debt.

In April this year, Silicon Valley Bank blew up because the value of its assets or collateral – US Treasury bonds – fell in value. The reason was the decision by technocrats at the Federal Reserve to tighten monetary policy – that is, hike interest rates. In other words, Silicon Valley Bank’s collateral - older bonds that paid out 1% in interest, say - now paid out less than new higher interest Treasury bonds. So older bonds (collateral) lost value.

SVB’s failure was the first signal that debt deflation was taking hold…

If investors and creditors sense that the borrower’s collateral (say the value of the Treasury bond or house) has fallen - they will demand immediate repayment, and/or make a dash for the exits.

Silicon Valley bank had also greatly expanded a particular, deregulated, loan to ‘private’ equity funds. The loans are known as subscription lines of credit (SLC). Subscription lines provide credit directly to private equity funds and are collateralized by the fund’s right to call capital from limited partners, as Sissoko explains.

From 2012 to 2022 SVB’s subscription line lending increased from $1.7 billion to $41.3 billion and from 19% of its loans to 56% (Vardi 2023). This shift took place at a time when the bank was growing extremely quickly, as both total loans and total assets in 2022 were more than eight times their value at the end of 2012.

This was nothing less than deliberate debt (or credit) inflation.

The gainers were SVB’s uninsured depositors, mainly Silicon Valley tech executives - that made capital gains from the bank’s expansion of financial assets. As we know now, the euphoria was followed by a debt deflation that bankrupted the bank. However, this was an insolvency like no other. Sissoko again:

It was not, however, the bank’s failure that was remarkable – the US after all has a long history of poorly managed medium-sized banks that are taken over by the FDIC with losses imposed on uninsured depositors – and a 2018 law had explicitly determined that a bank the size of SVB should not be treated as a “systemically important financial institution” (Valladares 2023).

What was remarkable was the decision [by the Federal Reserve] to protect SVB’s uninsured depositors from any losses.

It appears debt deflation may be dangerous for you and me, but is not disastrous for the Fed’s favoured few.

That is why it is important for debtors to beware a turn in the credit/debt inflation tide.

[i] World Economic Outlook: Growth and Institutions, (Washington DC; IMF, 2000, p.13)

Carolyn Sissoko, 27 August, 2023: Private Equity is a Misnomer: Government Support Has Been Driving the Restructuring of US Corporate Structure and the Transfer of Wealth to Buyout Firms Over the Past 40 Years.

J.K. Galbraith, 1954, p. 86. The Great Crash

As above, p. 70. The Great Crash.

A very clear explanation and sadly prediction. As a matter of detail I couldn’t relate the 269% and 286% total debt figures in the text on the related graph.

For a decade until my retirement in 2005, I tracked residential property markets for the U.S. GSE Fannie Mae. What I learned is that our property markets (and those in most other countries) are plagued by the hoarding of land and by land speculation. Economic theory confirms that the only real solution is to impose an annual tax on owners of land equal to the potential annual rental value of whatever land is held, ideally eliminated the burden of taxation on housing units. What is not discussed is the fact that while housing is a depreciating asset that requires continuous expenditures for maintenance and huge expenditures for systems replacement every decade or so, the value of land is (as every realtor tells us) based on the quality of the public goods and services in a given locality.

Absent the kind of property tax reform referred to above, the only strategy to be employed to increase the supply of permanently-affordable housing is for communities to put whatever land is held publicly into a land trust. Housing (whether for renter-occupancy or owner-occupancy) can then be constructed and leased or sold as prices set based on the household income of eligible households. To prevent unearned gains on any future sale of owner-occupied units, the selling price then needs to be set based on an appraisal (i.e., replacement cost, less depreciation).