After a week of scary wildfires in the suburbs of Athens; and of racist and fascist turmoil here at home on this small island… in which a mob tried to burn down a hotel that housed hundreds of trapped asylum seekers…

… I am back at my desk… with much to write about.

I want to begin with the dominant theme of today’s discourse: a theme heavily promoted by the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Rt. Hon. Rachel Reeves MP.

No, its not the need to use the power of the state to tackle and end public anger, inequality and poverty; to provide skilled, well-paid work and decent housing for millions of people whose low incomes make renting or buying a home unaffordable.(Some of the rioters charged with violent offences were found to be of ‘no fixed abode’.)

Nor is it to restore dignity and hope to those four million voters that voted for a proto-fascist party, Reform, and that feel, according to YouGov polling

that ordinary working people do not get their fair share of the nation's wealth (73%). They likewise think that the rich should be taxed more than average earners (69%), but at the same time think that welfare benefits are currently too generous (60%).

Nor does the Chancellor feel that there is a need to use the power of the state’s finances to seriously prepare the British people for the threat of climate breakdown and nature’s collapse. In other words, to fulfil the ultimate purpose and responsibility of the state and its Chancellor: the provision of security to its citizens. (The Greek state patently failed that responsibility to citizens of Athens last week. The political and economic cost will be high.)

No, the new Chancellor’s dominant theme is nothing less than ‘growth’ - the answer to all our prayers.

It is, we are told, the answer to the British establishment’s all-consuming obsession with government spending and the public finances. An obsession not limited to Her Majesty’s Treasury (HMT), the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR), to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) or to orthodox economists. An obsession shared by most ‘post-Keynesian’ economists convinced the public finances merit positioning above other forces (including monetary and international forces) shaping the broader economy.

Most of these organisations treat the nation’s finances, and loose fiscal policy as causal of decline. And ‘growth’ as the answer.

Cutting the deficit and debt is deemed essential for recovery - and ‘growth’.

I disagree.

Public debt and deficits must be understood instead as the consequence of the post 2010 era historically low levels of public and private investment; of falling wages and of economic stagnation. The debt and deficits are an outcome, not a cause of economic failure.

When (as in the pandemic) the economy craters - the public debt and government deficit rises.

As night follows day.

When the economy prospers, public debt and deficits fall - and balance is restored.

When as now, the economy continues to stagnate, and the government (like the private sector) fails to finance the investment needed to drive the recovery and economic security, expect public debt to remain stubbornly high.

When as now, the Bank of England ignores its monetary policy mandate

(a) to maintain price stability, and

(b) subject to that, to support the economic policy of Her Majesty’s Government, including its objectives for growth and employment.

When the Bank’s monetary policies (high interest rates and Quantitative Tightening (QT)) work instead against government aims and objectives (including those of the recent Conservative government) expect public debt to remain high.

In these circumstances austerity is not the answer.

As Keynes once said in conversation with Sir Josiah Stamp (a conversation published in The Listener in 1933) in response to Stamp’s concerns about the “unbalanced Budget”:

But, my dear Stamp, you will never balance the Budget through measures which reduce the national income. 1

The new Chancellor apparently disagrees. (I say ‘apparently’ because much of what passes as political discourse at the moment seems ‘performative’. They are simply attempts at a narrative intended to ward off attacks from the enemy, while behind the scenes something different might be going on. For example, the Chancellor has just agreed the appointment of an anti-austerity economist, Professor Alan Taylor, to the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England.)

I am being generous here, because in an attack I am inclined to take personally, the Chancellor’s marketing team crafted a neat rebuttal to the very first sentence of my last book, The Case for the Green New Deal. It was:

We can afford what we can do

No, the new Chancellor replied in a BBC interview on 30 July, 2024.

If we can't afford it, we can't do it.

I will not be daunted by this sophistry - and nor should you be.

A few days after the British general election of the 4th July, the Treasury issued the following statement:

The Chancellor has today (8 July) promised to take immediate action to fix the foundations of the economy, rebuild Britain and make every part of the country better off.

Addressing the difficult economic inheritance this government faces, she committed to taking immediate action to drive sustained economic growth, the only route to improving the prosperity of our country and the living standards of working people.

Her publicly stated argument appears to run like this: to stabilise the public finances, to ‘balance the books’ it is necessary to use austerity to reduce the national income by amongst other measures, cutting a winter fuel allowance for pensioners, capping welfare benefits to large families and slashing the proposed £28billion investment in the Green New Deal.

That, it is asserted - will ‘fix the foundations… rebuild Britain’ and stimulate ‘growth’.

We shall see.

What’s ‘growth’ got to do with it?

“Growth” is a term used by economists and politicians aiming for an expansion in economic activity: an increase in investment, employment, and the output of goods, and services. Conversely, it is used in a pejorative sense by environmental campaigners convinced that the endless expansion of economic activity in a world of finite resources is unsustainable. Its antonym, “degrowth,” is deployed instead, as in The Future Is Degrowth: A Guide to a World beyond Capitalism.

Surprisingly, the use and evolution of “growth,” and its link to GDP, represent an important stage in the development of today’s international financial system - based as it is on expectations of continuous “growth” facilitated by international financial deregulation and capital mobility. ‘Growth’ which since the 1960s, and in the context of financialized capitalism has led to ecological, social, and economic imbalances that threaten systemic failure.

The Origins of “Growth” and Deregulation

The story starts with British economist John Maynard Keynes. Back in the 1930s, Keynes played a far greater role in the creation and construction of the UK’s (and ultimately the world’s) national accounts than is usually recognized. He did so not for the purpose of accounting, but to assess the existing level of income against the potential level of income under certain policy conditions.

The value of what was then known as the “national income,” and which came to be defined by Simon Kuznets as ‘GDP’, was of minor interest to Keynes. As Geoff Tily explains, Keynes regarded the development of such accounting as a means to an end, not an end in its own right. “The national accounts were developed to support policy: to resolve the unemployment crisis of the Great Depression and to aid the deployment of national resources to their fullest possible extent for the conduct of the Second World War.” It is important to recognize, Tily continues, that

these theoretical and practical initiatives were aimed at the level of activity—at the increased and then full employment of resources and the full extent of national production—rather than the growth of activity. At this stage there was no notion on the part of policymakers that the level of activity might be encouraged to grow in any systematic or uniform way from year to year; the intention was achieving one-off level shifts. (Emphasis added).

The “Growth” Revolution

Keynes’s approach to national accounts changed radically in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In the United Kingdom, various professional economists—not least Sir Samuel Brittan, prominent columnist at the Financial Times—championed a new concept of continuous “growth” and defined themselves as “the growthmen.” It was an approach that changed the character of policy over the postwar age. Abandoning the aim of fixing the level of employment and output to sustainable levels, governments would set a systematic and improbable target: to chase growth. Nobody seems to have paused to consider whether growth—derived as the rate of change of a continuous function—was a meaningful or valid way to interpret changes in the size of economies over time, writes Tily.

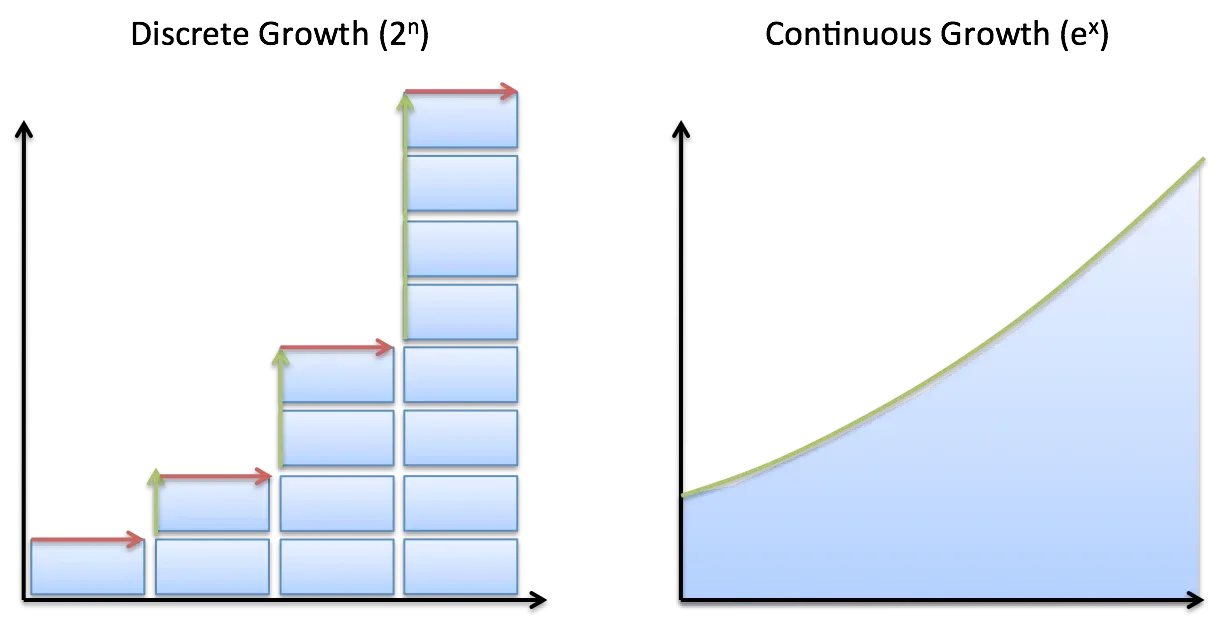

Illustration source: “Better Explained”

In parallel, economic policy increasingly emphasized supply-side approaches, and hence a practical commitment to increased deregulation of economic activity. This is exemplified by the Council of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) adopting on September 12, 1961, a “Code for Liberalisation of Capital Movements.” This code, a framework for the progressive removal of barriers to cross-border capital flows, presumably was designed to enable what Tily calls the

ludicrous ambition of rapid and relentless growth, regardless of the extent of capacity in the labour market.

In October 1961, the OECD held a conference on “Economic Growth and Investment in Education” at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC. Encouraged by “classical” economists and discouraged by what (compared to today’s standards) were high yet sustainable levels of economic activity, the OECD proposed to turbo-charge the UK’s and other economies. At the time, the United Kingdom was in the happy position of providing full employment. In the words of then prime minister Harold Macmillan, Britons had “never had it so good.” On November 17, 1961, the OECD agreed to a 50 percent growth target for the UK for 1960 to 1970. The OECD target was equivalent to 4.1 percent per year. At the time, the British unemployment rate was 1.2 percent.

The result of this overly ambitious goal-setting was entirely predictable—an era of rampant inflation in the 1970s, followed by periods of financial excess and recurring crises. The blame for this inflation has since been laid squarely, and unfairly, on the shoulders of Keynes and on the labor movement.

In fact, the attempt to achieve a wildly implausible growth target in conditions of near full employment led to the undoing of Keynes’s legacy: the “golden age” of capitalism from 1945 to 1971. Above all, it led to the dismantling of the system of managed global economic governance established at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944.

This essay is part one of two articles emerging from the Carnegie Working Group on Reimagining Global Economic Governance, and commissioned by Stewart Patrick of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Keynes’s conversation with Stamp can be found on page 103 of a book titled ‘Keynes on the Wireless’ published by palgrave Macmillan in 2010.

I try to write about economics in a way that accounts for morality, power, class and history, and makes sense to non-economists. What keeps me going - and grateful - are the people who, by paying for a subscription when they don't have to, show confidence in my work.

Excellent. Could not agree more.

For the last 50 years (at least) economists, journalists, and reporters have all been educated in an economic monoculture. Is it any wonder that none of them can think outside the box? Those not trapped in the current dystopian paradigm are rare. You are a gem, Ann.

Labour had no comeback to the vicious Tory criticisms following the 2010 election. I never understood why they failed to defend their economic program and let the Tories walk all over them.

Following Osborne & Co, the public now all think that the national finances are run like a chequebook and they won't stand for any other narrative. Being unable to beat the Tories, Labour have joined them.

Labour didn't win the last election, the Tories lost it. Labour's goal now appears to be to replace the Tories by *becoming them*. Labour are now a neoliberal party, pursuing a neoliberal economic agenda. The fact that it *won't work* doesn't seem to matter to Labour any more than it mattered to the Tories.